Illustration: Shyam G Menon

Long read

2020 – What can one say of it? It was the year with a numerical elegance to it. In the end, it ended up a contest with an infectious virus that infected millions and claimed thousands of lives. Many countries announced lockdown leaving people stuck indoors. Sports ground to a halt and sporting events worldwide – including the 2020 Tokyo Olympics – were postponed or saw their 2020 edition cancelled. As lockdown eased, signs of activity emerged. Distance runners set a series of new world records; in India, Avinash Sable set a new national record in the half marathon. The Tour de France happened, a few major city marathons were held in the physical form restricted to just elite athletes. The 2020 Airtel Delhi Half Marathon (ADHM), the only major road race since March to put feet on the ground in India, had its physical version confined to participation by elites. However in early January 2021, the organizers of the Chennai Marathon are expected to pioneer a bigger experiment – a run capped at a maximum of 1000 participants on a closed circuit at a location away from the city. The website of the Association of International Marathons and Distance Races (AIMS) lists a handful of races from India in its calendar of events spanning January-February 2021; among them are the IDBI Federal Life Insurance New Delhi Marathon and a rescheduled, scaled down format of the Tata Mumbai Marathon (please note: such listings aside, the final picture is as available from event website). Meanwhile Bengaluru’s well known bicycle racing championships – BBCH – has resumed and there is a trickle of ultramarathon, trail running and ultracycling events beginning to happen.

During the pandemic, a healthy lifestyle with adequate exercise found fresh respect. The World Health Organization (WHO) went so far as to say: every type of movement counts. It was a reminder of the toll modern lifestyle had been quietly taking. Realizing the virtue of fitness amidst pandemic, the number of people resorting to a morning walk or run, increased. Cycling is an environment friendly and healthy mode of personal transport. It experienced resurgence. Bicycle stores worldwide saw stocks deplete causing waiting lists to manifest at some. Procuring fresh stocks was tough because manufacturing units and global supply chains were already impacted by the altered normal of pandemic. All in all, 2020 while painful was a mirror to human existence. Nothing highlighted humanity’s effect on the planet like the clean air of absolute lockdown and the images of wildlife exploring deserted streets. Nature found a breather to rejuvenate. It put us and our ways in perspective.

Amidst all this, one major trend that happened in sport was the rise of virtual events. It influenced endurance sports in varying degrees. Cycling was well placed to host this trend because its ecosystem already had a device capable of facilitating digital interface – the trainer. Running took a while to catch up but by the last quarter of the year, there were plenty of race apps and virtual events for runners to stay busy with. While they didn’t replace the appeal of a road race, in times of pandemic, virtual events were a reasonable alternative for those needing goals to motivate themselves. However, from the classic triumvirate of endurance sports, swimming – it is a sport that is firmly a composite of action and medium – was badly hit. In India, pools stayed shut for many months and when the government permitted reopening, it was for only competition swimmers. Not to forget – every sport is now an industry of gear manufacturers, retailers and service providers complemented by sectors that support like aviation, railways, public transport and hospitality; there has been impact in these segments as well. Those plotting revival of events like road races have to first accept that an entire ecosystem was rattled.

Through the lockdown and its progressive easing, this blog kept a conversation going with amateur athletes and a small number of elites. The end of a year provides opportunity to look back at the year as a whole and also look ahead. We spoke to runners, cyclists, doctors and race organizers:

A familiar picture from Mumbai running – Girish with backpack (Photo: courtesy Girish Mallya)

Runners in Mumbai know there is something missing. The third Sunday of January is usually when Mumbai hosts the annual Tata Mumbai Marathon (TMM), India’s biggest event in running. For the city’s runners, the post-monsoon months are dedicated to training for TMM and the category of race one registered to participate in. It has been different in the last quarter of 2020. At the time of writing in December, there was still no official word on the fate of the annual marathon although the website of the Association of International Marathons and Distance Races (AIMS) listed in its upcoming calendar of events, a rescheduled and scaled down version of TMM for February 28, 2021. Sources close to the race organizers confirmed ongoing discussions with government in this regard. For now, given no official information yet on the race website and the general awareness that COVID-19 will allow only a scaled down format even if a physical event happens, there is little of the regimented training to peak performance that runners at large chased in December 2019. There is a vacuum and Mumbai’s amateur runners know it as they jog into the New Year. “ I really wanted to participate in the 2021 TMM,’’ Girish Mallya, who has run every edition of the annual marathon since its inception in 2004, said. He would have liked to run at least 20 editions of the Mumbai marathon without missing any. `He runs because he likes the activity (he is known to jog home from office, after work); he also generally trains alone. He doesn’t find anything particularly appealing in virtual races because he already knows the solitude of running by himself. That is what made the city’s annual marathon special – it brought forth the community of runners, not just from Mumbai but from various parts of India and overseas. It gave a sense of being with and around others. However COVID-19 caused cancellation of races and the trickle of events resurfacing after lockdown require them to be cast differently; basically scaled down, to suit the safety protocols of the times. Girish reached out to the organizers of TMM suggesting that a 2021 edition – if there is one – be whittled down to just the full marathon and any physical race happening as a result also accommodate amateurs who have remained loyal through the years. “ If nothing happens, then I will make an exception to my indifference towards virtual formats and run the virtual TMM in the New Year,’’ he said.

Srinu Bugatha at 2020 TMM (Photo: Chetan Gusani)

Going into 2020 ADHM in November, Srinu Bugatha was the defending champion among Indian elites. He finished second in 1:04:16. That race behind him, by end December, Srinu was training for the New Delhi Marathon of February 21, 2021. “ I feel good,’’ he said. In January 2020 Srinu had finished first among Indian elites at the year’s TMM in Mumbai with timing of 2:18:44. Two months later when the lockdown set in, he shifted to his village in Andhra Pradesh from the Army Sports Institute (ASI) in Pune, where he normally trains. By around June he was back at ASI but had picked up an injury. It progressively led to a pause in his training. He then spent roughly two months resting, allowing the injury to heal. It was around October that Srinu recommenced his training. Regaining form takes a while. ADHM also happened at rather short notice. That won’t be the case with New Delhi Marathon. The event will be his first shot at qualifying for the marathon at the Olympics since COVID-19 blanketed the planet and the Tokyo Olympics was postponed by a year to 2021. The qualification is a challenge – for the men’s marathon, the entry standard is 2:11:30 (source: Wikipedia); faster than the current Indian national record of 2:12:00. The window to qualify continues till the end of May, 2021 and it is expected that more races would slowly start to open up worldwide in that period for athletes seeking to make the cut for the Olympics.

Jigmet Dolma (left) and Tsetan Dolkar; after 2020 TMM (Photo: Shyam G Menon)

December, 2020 is different for Jigmet Dolma. For the past several years, the young Ladakhi runner, her running partner, Tsetan Dolkar and a team of runners from Ladakh were a regular fixture in a Mumbai drifting to year-end. They would arrive weeks before the annual marathon, train in the city under Coach Savio D’Souza and participate in TMM, typically securing a few podium finishes in the race. Jigmet and Tsetan used to run in the Indian women’s elite category. In the 2020 edition of the race Jigmet had placed fifth among Indian elite women, covering the course in 3:05:09. Tsetan finished in 3:05:12, to place sixth. Their participation in TMM was part of a larger program conceived and supported by Rimo Expeditions, enabling Ladakhi runners to compete in races in the plains. Coinciding as the trip did with North India’s winter, the months away from home also spared the runners Ladakh’s cold. It let them train properly. COVID-19 changed that. With India slipping into lockdown in March and most road races cancelled worldwide, this winter Jigmet and her fellow runners are in Leh. “ All of April I didn’t run. I rested. I started running locally and for short distances in May. It wasn’t possible to venture far because those days restrictions were strict,’’ Jigmet said, late December. Things slowly changed. She would manage an hour of training in the morning and an hour in the evening. She did strengthening exercises. The distance she could cover under the prevailing conditions of pandemic also increased; on Sundays she put in a long run of 25 kilometers. Asked how she motivated herself given there were no races to look forward to, Jigmet said, “ I kept telling myself, my chance will come.’’ She hasn’t resorted to any virtual race. Winter is a challenge for runner in Leh. Mumbai’s much warmer Marine Drive, where the team trained in December 2019, seems a long way off. “ Usually in Leh, I train early morning around 6.30. Now it is much later; you have to adjust it according to the cold,’’ she said.

Thomas Bobby Philip (Photo: courtesy Chetan Gusani)

Prior to the lockdown, which commenced in March 2020, Bengaluru-based amateur runner Thomas Bobby Philip had made plans for the year. He wanted to travel to ten cities in India and run there, in the process meeting more fellow runners and those associated with the sport. The virus ensured that the project went into cold storage. Instead, as lockdown took hold, Bobby found himself deprived of his daily dose of running for seven straight weeks. As he put it, those weeks were a mixed bag. On the one hand, stuck at home, he was spending more time with his family and that felt fine. On the other hand, the runner in him suffered; the house arrest led to an erosion of his motivation to run. “ Before the lockdown; during the past eleven years I hadn’t stopped running for more than a week. Anyway, I don’t look back and question or judge what happened in 2020,’’ he said. Bobby was among those who used the lockdown to focus on workouts. He did strengthening exercises. “ My focus on strengthening grew exponentially,’’ he said. Then as the lockdown eased, he started the journey of getting back to running. After seven weeks lost to another reality, it was a challenge regaining the motivation to run and re-establish the erstwhile momentum. There were no races too on the horizon to serve as goal and lead runner on. “ Still I think I have managed well,’’ Bobby said. He was doing 10 kilometer-runs in sub-39 minutes, which wasn’t significantly off the sub-37 timings he was returning in the days before lockdown. One emergent trend was helpful – virtual races. At the time of writing, Bobby had done a virtual marathon organized by Nokia, the virtual version of the Airtel Delhi Half Marathon and was due to run the virtual format of the TCS World 10k. The full marathon happened in October; it was his first run of that distance since Bobby’s participation in the 2020 Tata Mumbai Marathon in January. He started training for it only about five weeks in advance. He completed the marathon in three hours, one minute (3:01), which was an improvement over his pre-lockdown timing at 2020 TMM (3:07:49 / the performance was affected by a preceding phase of illness). It was also in line with the reputation Bobby had come to garner in his age category – that of a runner finishing the marathon in around three hours to slightly less than three. “ In Bengaluru, life is almost back to normal for those pursuing the active lifestyle. When it comes to groups, the difference is people don’t congregate in big numbers. There are the safety protocols prompted by pandemic to follow,’’ Bobby said. A regular podium finisher at the races he used to participate in, he said that notwithstanding the relief offered by virtual races, nothing can replace the ambiance of an actual road race. The absence of events continues to be sorely felt. There is hope – in November, the 2020 ADHM featured a physical race restricted to elites and in January, the Chennai Marathon is due to try out a physical version capped at 1000 runners. But with news of virus mutation too around, it is still fingers crossed and proceed with caution as 2020 gives way to 2021.

Naveen John (Photo: courtesy Naveen)

Late December 2020, Bengaluru-based Naveen John, among India’s top bicycle racers, was kicking off a new training project in Hyderabad. He had shifted to Telangana’s capital to train for the Individual Time Trial (ITT) at the velodrome in Osmania University. “ The goal is to become competent in ITT over the next 40 days and become competitive by April 2021,’’ Naveen said. Guiding him online would be his new coach – Ashton Lambie. A track cyclist who has represented the US, Lambie is a former individual pursuit world record holder. Naveen’s temporary shift to Hyderabad is happening some nine months after the lockdown was first announced. In the early part of the lockdown, when everyone was expected to stay indoors, he had embraced virtual cycling platforms and kept up his training as best as he could. It required, some rewiring of cyclist’s motivational circuitry as the freedom of being out and the outdoor environment, were suddenly missing from the frame. By late May, his training had been good enough for Naveen to muse that if there was a national competition due, he would do well. Given progressive relaxation of the lockdown, he had also regained the freedom to cycle outdoors. What was missing however was a “ horizon.’’ He could rationalize the lockdown in many ways – for instance, it can be treated as similar to a phase of injury, something athletes are used to – but the lack of endgame and races had been unsettling. “ Previously my plans used to span three to four weeks. Now I am taking it one week at a time,’’ Naveen had said then. Slowly things have changed since. In November the Bangalore Bicycle Championships (BBCH) resumed its monthly race. Naveen won the December edition of the race. Amidst all this, there were a few other challenges. As lockdown eased in India and elsewhere, bicycle sales shot up. It led to never before seen waiting lists to buy cycles; the breakdown in global supply chains also put strain on availability of spare parts. Anticipating something of this sort, Naveen had stocked up on essential components in the days leading to lockdown. Elite cyclists train harder and longer than recreational cyclists. This causes more wear and tear to equipment. Despite his preparation, Naveen wasn’t spared. A shifter on one of his bikes malfunctioned and a new shifter to replace it couldn’t be obtained. Luckily, his predicament was noticed by helpful others and the required import from overseas was managed. Someone who races in India and overseas, Naveen is hopeful that more events will return in 2021. After all, notwithstanding pandemic, the 2020 Tour de France was held. And in India, a timeframe has been assigned for the 2021 nationals in cycling.

Seema Verma (Photo: courtesy Seema)

When the country went into lockdown in late March, runners who were dependent on the prize money that accompanied podium finishes at races were left in great difficulty. They used to bank on prize money to bridge the gap between living expenses and the modest income they earned through other means. Seema Verma, resident of Nalasopara, a suburb of Mumbai, had to rethink how she would make ends meet. Many years ago, she had worked as a domestic help after she was abandoned by her husband. In the initial days of the lockdown, with the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic, she had briefly contemplated going back to that role. Some running groups and individuals extended her support in terms of money and supplies for home. “ That help came as a major relief to me,” she said. During the early phase of the lockdown, she was completely confined to her one room-house. “ I did my core workouts and took to running inside my small house daily. I used to do 10 km runs inside my house and once I managed up to 17 km,” she said late December. When the lockdown norms began easing, she started stepping out for her runs, increasing the mileage slowly. But the absence of regular income remained a constant worry. She then started a flower vending business. “ Many years ago, I used to sell vegetables on a cart near the place where I stay. This time around, I decided to opt for selling flowers and bouquets,” she said. The business is risky as flowers do not have a shelf life longer than four days. “ On some days, the sales do not cover the cost,” she said. Seema wakes up early and goes for her run by 5.30 AM. “ Upon getting back, I set out for the market in my running clothes, to buy stuff. After that I shower and leave for the vending business,” she said. Her stall stays open from 9 AM to 12 noon and from 5.30 PM to 9 PM. On some days of the week, she misses her run as she has to be in the flower market to buy fresh flowers. “ If I land up late at the market, I get old, wilting flowers,” she said. Her son, now 19-years-old, has secured employment and his earnings help the mother-son duo to pay the rent for the house. Her running mileage is now around 15-20 km and on some days she does a half marathon. Recently, she did a 12-hour trail run in Pune and finished as the overall winner covering 67.2 km. But there was no prize money. “ I knew there was no prize money but I wanted to do a run before the end of the year,” she said. Seema is conscious of the fact that prize money races are still a long way, at least another six months away.

Ashish Kasodekar; from the 2019 edition of La Ultra The High when he became the first Indian to complete the event’s 555k race segment (Photo: courtesy Ashish Kasodekar)

In January 2020, Pune based-ultramarathon runner Ashish Kasodekar had completed the Brazil 135. By the end of that month, the first case of COVID-19 was reported in India but the rapid spread of infection leading to lockdown, was still some distance away. For those loving elegance in digits, February 20 was a special day; it was the 20th day of the second month of 2020. In some ways that perception betrayed the general optimism that greeted 2020, it had a nice ring to it. Ashish observed that day by hiking up Sinhagad fort near Pune, 16 times over 31 hours. The exercise provided a cumulative elevation gain matching the elevation of Everest. A major project in the months ahead was the 2020 edition of the Badwater Ultramarathon in the US; Ashish had secured a slot to participate in it. The virus decided otherwise. By March 24, India was into lockdown. Ashish followed the lockdown rules diligently. He kept himself busy indoors with a multitude of challenges from various sports communities including those into basketball, a sport he loves. He did strengthening exercises and watched motivational videos. There was also a book he had long wished to write; the lockdown proved ideal for the task. “ I didn’t find the lockdown period very troubling. I think most people who keep themselves busy with things to do would have managed it well,’’ Ashish said. He also admitted that as an ultramarathon runner, he may be used to existence as a litany of changes. During very long distance runs like an ultramarathon, athletes endure changes in weather, elevation and their own physical and mental condition. So a period of world gone indoors and mobility restricted can be mentally rationalized, alternatives to stay occupied, found. A travel consultant, Ashish’s business took a hit during the pandemic as globally, people cut down on travel drastically. He improvised. He commenced a mentoring program for those who wish to do something in life. He also started a camping trip with accompanying activity in the outdoors, done every full moon. But end December 2020, it was his fiftieth birthday due in 2021 that was keeping Ashish focused and fueled. He had commenced a personal project – visit 50 forts (the Sahyadri hills of Maharashtra have plenty of forts), plant 50 trees hailing from varieties indigenous to India, take 50 people out for lunch and run 60 marathons in 60 days. And if all goes well with the world, he should be in the US for the 2021 edition of Badwater.

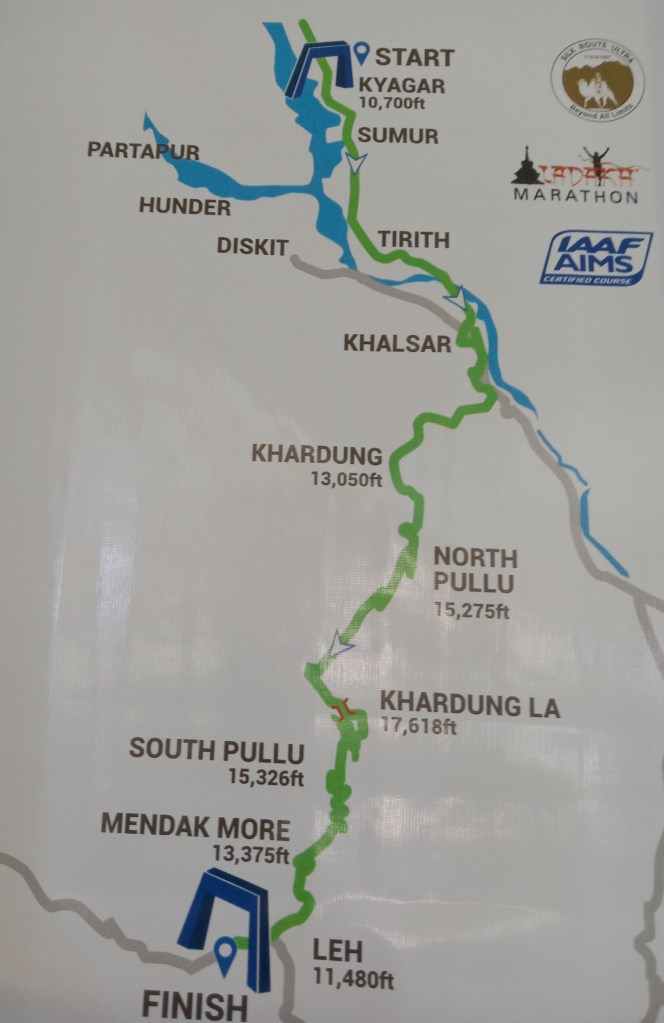

Bharat Pannu; from virtual RAAM (This photo was downloaded from the cyclist’s Facebook page)

For ultracyclist, Lt Col Bharat Pannu, 2020 was a keenly anticipated year. His earlier attempt at Race Across America (RAAM) had failed to take off following injury while training in the US, just ahead of the 2019 race. He was therefore determined to do RAAM in 2020. The onset of pandemic and the cancellation of races worldwide – including RAAM – was a setback for Bharat. RAAM is one of the toughest ultracycling events; anyone participating has to put in oodles of effort by way of training and preparation. For the second consecutive year, RAAM wasn’t happening for Bharat. Luckily, even as the real race got cancelled, a virtual version of it was made available by a technology platform in league with the race organizers. Bharat registered for it. What followed was a genuine high point in distance cycling by Indians, in a year impacted by COVID-19. Cycling on a stationary road bike in Pune along with friends who had signed up for the virtual version of the shorter Race Across West (RAW – a smaller race built into RAAM), Bharat completed RAAM and secured third place on the podium. He then moved to the virtual version of HooDoo 500, a race of approximately 850 kilometers and completed it in 41 hours, 25 minutes. Next he did a 12 hour-time trial and finished in third place, covering 390.4 kilometers in the allotted time. On October 10, he set out from Leh in Ladakh to attempt a record for cycling the Leh-Manali stretch. The authorities at Guinness Book of World Records assigned him 40 hours for the task. Bharat covered the distance in 35 hours, 25 minutes. Days later, he covered the 5942 kilometers of India’s Golden Quadrilateral (a series of highways linking the major metros of the north, east, south and west) in 14 days, 23 hours and 52 minutes. Details of the Leh-Manali and Golden Quadrilateral projects have been submitted to Guinness. “ Official ratification is awaited,’’ Bharat said, late December. Looking back, he felt he may have come off virtual RAAM and the third place he got in it, with a lot of positivism and good energy. It led him on to HooDoo 500, Leh-Manali and Golden Quadrilateral.

Apoorva Chaudhary (Photo: Bounty Narula)

“ It was a roller coaster ride,’’ Apoorva Chaudhary said of 2020. An ultramarathon runner who has represented India, at the start of the year she was focused on already announced international events like the Asian championships. The last event she participated in was the 2020 New Delhi Marathon, which she had treated as a training run for races ahead; that was in February. Roughly a month later, India entered lockdown. After a month stuck indoors in Gurugram and with work from home the new norm, Apoorva shifted to Bijnor to be with her parents. She continued her training and strengthening exercises there. Her coach monitored online. Things were fine for a while; then she began to lose her motivation. According to her, in the pre-pandemic scheme of things it was possible to rejuvenate a day of poor motivation to run by running in the company of one’s friends. With COVID-19 and its protocols blanketing the world, people drifted apart. Old remedies to tackle monotony weren’t available. This was a real low point. Apoorva realized she needed a change. She temporarily shifted to a homestay in a village near Dehradun; a sort of `workation.’ More important, she decided to pick up a new skill – horse riding, for which she associated with a local school that maintained a stable. “ It was a longstanding desire anyway,’’ she said. At the same time, she continued her running in the village. The experience helped her regain her motivation. As regards training, Apoorva said that her focus has been on strengthening exercises and a volume of running that is short of peak levels. The idea is to hang around in that stage of fitness where a few weeks of determined training will take her to peak condition. At the time of writing, Apoorva was back in Bijnor but there was a potential new recipe on the cards for the new normal. The hills offer fine refuge for her interests; she may take off again.

Kieren D’Souza; running in the mountains (Photo: courtesy Kieren)

2020 was a special year for Kieren D’Souza. For the past several years he has based himself in Manali but spent a few months every year overseas participating in events there. With the pandemic pausing sport events worldwide and crippling international travel, Manali became Kieren’s world. An ultramarathon runner and more importantly an aspiring mountain athlete, the predicament suited him as he was able to spend more time in the mountains that had become his training ground. On June 16, 2020, he had run from Mall Road in Manali to the base of Friendship, a 17,352 feet high-peak and then made his way light and fast to its summit. It took him seven hours and fifteen minutes to reach the summit from Mall Road. He then descended and ran all the way back to Mall Road. With that effort Kieren had hoped to kick-start the culture of Fastest Known Time (FKT), a tradition that is well established abroad. Towards the end of August, he embarked on another project. With Mall Road again as start line, he ran from Manali to Hampta Pass (14,009 feet) which brought him to Lahaul and from there over the Rohtang Pass (13,051 feet) back to Mall Road in Manali. Then in October, he elevated the game to a whole new level. This time he didn’t start from the town’s Mall Road. The objective was Deo Tibba (19,688 feet). The road head for accessing it was roughly a half marathon away from town. So the run was designed as road head to road head instead of Mall Road to Mall Road. He did a recce of the route on the mountain. For the actual attempt, a support group of individuals pitched in; they were spread out along the mountain slope and manned three camps where Kieren also parked his mountaineering gear in advance. On October 1, he commenced his run from the road head. Past base camp, he moved up Deo Tibba alpine style and without using any ropes. At the concluding portion of the climb to the summit, he and a friend roped up briefly for safety but used no ice screws or any such protective equipment. The entire passage from road head to road head took him 19 hours, 38 minutes, Kieren said. With the project finding a sponsor in the skin cream brand Nivea, a related film was also made. This model of activity and documentation using media appears sustainable going ahead, Kieren said. It may be some time before the pandemic settles to containable proportion and the world is back to relaxed mode and travel as before. But if the paradigm of existence he discovered in 2020 sustains, Manali can continue to be a productive year round base for his pursuits, Kieren felt. Viewed so, 2020 was an interesting year for the young man trying to live his dream of being a mountain athlete.

Gopi. T (blue vest) at 2018 TMM. Just behind him is Nitendra Singh Rawat; they finished first and second respectively in their category (Photo: courtesy Yogesh Yadav)

For Gopi. T, among India’s best marathon runners, 2020 has been a year of inevitable downtime catching up. The elite athlete had transitioned from 2019 to 2020 with a persistent leg injury. But he soldiered on as it was an important year for athletics – the Tokyo Olympics was due and he had to qualify for it. He skipped the 2020 TMM held in January. He set his eyes on major marathons like the Tokyo Marathon, Seoul International Marathon and London Marathon – they have a better course and typically more favorable weather conditions – for a shot at qualifying for the Olympics. In March 2019, Gopi had got his personal best at Seoul, when he completed the marathon in 2:13:39 (it is the closest any Indian runners has come yet to the longstanding national record of 2:12:00) and placed eleventh. One reason for valuing course and weather conditions in 2020 was that Olympic qualification required meeting an entry mark of 2:11:30. It is a challenge. Part of the national camp, he was assigned to train in Bengaluru. But Gopi’s injury slowly worsened. By the time lockdown set in, he was scheduled for knee surgery. Post-surgery, he was advised bed rest for close to two months to help the healing. In June the first steps in rehabilitation commenced. He continued his recovery and conditioning as best as he could; maintaining the momentum when he traveled home to Wayanad in August, as well. At that time, he could jog a short distance, walk and then repeat the mix again. Gyms hadn’t reopened in Wayanad. So Gopi did his strength training at home. Meanwhile, when the new list of athletes at national camps for the September-December period was disclosed there was nobody mentioned under the category of men’s marathon. Upon return to Bengaluru, Gopi continued his strength workouts and jogging on his own, outside the premises of the Sports Authority of India (SAI). At the time of writing, he was back to running but it had to be done carefully because there was an occasional pain on his left knee. “ I can do up to 30 minutes on the treadmill now,’’ Gopi said, late December. Needless to say, qualifying for the Tokyo Olympics looks doubtful. “ I think the reasonable option for me would be to focus on the Asian Games of 2022 and train accordingly,’’ Gopi said.

Anjali Saraogi; from the Asia Oceania 100K Championships in Aqaba, Jordan (Photo: courtesy Anjali)

Kolkata based-Anjali Saraogi used the period of lockdown to catch up on her strength training. Among India’s top ultramarathon runners, she invested in gym equipment and worked out at home. In terms of running – an act that requires person foraying out from home amid pandemic – she chose to play it safe so that none in her family were put at risk. It was June by the time she could venture out for running and even then, she was limited by the fact that the locality she lived in was often in and out of being a containment zone. That made it difficult to pile on mileage, something crucial if you are an ultrarunner. “ The 1-2 hours of running most amateur runners do, does not suffice for us. We need 3-5 hours at times’’ Anjali said. In the past one month or so things have been better. Case numbers have slowly declined and there is a sense of normalcy returning. Consequently, Anjali’s running too has benefited from the improvement in overall ambiance. Asked if the challenges of 2020, including the way it hampered training for long distance runs, had imposed a lengthy curve to regaining form on India’s ultrarunners, Anjali said that a few months of consistent training would be all that is required to get back to form. Further, from among known ultrarunners, there are those who managed to take off to the hills periodically or shifted for long periods that side to train. Such locations have comparatively less people than India’s crowded cities and case numbers have also been less. Needless to say, training has continued better in those parts. “ The difficulty has been for those running in the cities,’’ Anjali said. About 2021, she believes that things should improve post-March and after June-July life should be much closer to normal. However, even as running events recommence, Anjali said that people may warm up to it only gradually as an element of confidence and safety in travel has to be felt at large. This could take time. “ Basically as regards 2020, I feel thankful for all the blessings I have in my life. The safety and good health of my loved ones – that has been the priority,’’ she said.

Vijayaraghavan Venugopal (Photo: courtesy Vijay)

In February 2020, when Vijayaraghavan Venugopal participated in the 2020 IDBI Federal Life Insurance New Delhi Marathon, the virus had reached India and was on the cusp of becoming a global worry. But few anticipated the rapidity with which things happened thereafter culminating in a massive, lengthy lockdown. “ It was an unpredictable year,’’ Vijay said, late December. The CEO of the sports nutrition brand Fast&Up is also a well-known amateur runner with podium finishes in his age category. “ From the world majors, I have the London and Tokyo marathons left to participate in. I also want to do New York again to attempt a sub-three hours-finish. I applied for New York but didn’t get through. After the New Delhi Marathon I was hoping to try the Airtel Delhi Half Marathon and the TCS World 10k. None of that happened because of the pandemic,’’ he said. On the other hand, COVID-19 and the lockdown it forced gave Vijay 2-3 months away from running. That was useful to both heal a longstanding injury and to reflect. One of the outcomes has been a growing interest in the shorter distances – 5k and 10k. Traditionally these distances have been important to groom marathon and half marathon runners. In India however, while the elite athletes usually follow above said path, most amateurs launch off straight into the half marathon. “ Over the last few months, I have been looking more at 5k and 10k. Hopefully, that should stand me in good stead when things improve in 2021,’’ Vijay said. A fan of racing events in the physical sense, he didn’t do any virtual runs. “ I look forward to the revival of actual races,’’ he said. His estimation is that following the elites-only ADHM of November and the proposed Chennai Marathon of early January 2021, a small number of events should emerge in the first quarter of the New Year. But it will still be touch and go and dependent on factors influencing overall sentiment like vaccine rollout, the nature of further mutations to the virus etc. The big events may be hesitant to return soon; the smaller ones associated with smaller volume of participation may be the first off the block. However, small volume-events may face the hurdle of financial viability as sponsors may stay off citing little mileage by way of publicity. “ Things should be clearer by the second half of 2021,’’ Vijay said. Having said that, he agreed there have been some new encouraging trends too as a result of the pandemic. On the average, everyone’s morning walk, run or bicycle ride is happening in an ambiance featuring more people out seeking to put in some exercise. It paints a unique scenario – one in which, races and the old racing focused approach to the sport may have receded temporarily but general interest in being physically active has likely grown. This newfound value in the physically active lifestyle is one of the less highlighted legacies of COVID-19. “ Recently Fast&Up hosted a virtual 5k run. There was a race with prize money and a run without it. The majority of people registering for the event were newbies to our website,’’ Vijay said.

Gerald Pde (Photo: courtesy Gerald)

Architect and runner, Gerald Pde, stays with his family roughly five kilometers away from Shillong in Meghalaya. That gives him access to the local woods. The way things played out, being near the woods was a blessing in times of pandemic and lockdown. The last event Gerald and the team of runners from Run Meghalaya, attended, was the Tata Ultra in Lonavala, held in February 2020. A month after that race, India entered lockdown. Back in Shillong, for Gerald and family, the first three weeks of the lockdown when it was fresh off the starting block and strictly enforced, were tough. “ After those three weeks, I started to venture a bit into the nearby woods,’’ Gerald said. It was a pleasant experience because in proportion to people gone indoors and the din and stress of human activity on planet diminishing, the local flora and fauna was staging a comeback. By May, Gerald had begun exploring trails in these woods. “ It was one of the positive sides of the lockdown. I got to know the smaller roads and trails better,’’ he said outlining how running returned to his life at this stage. Post September-October, things have drifted closer to normal. “ At peak physical condition in pre-pandemic days I used to log weekly mileage of 140-160 kilometers, sometimes a bit more. Now I am at around 100 kilometers,’’ Gerald, who is among the founders of Run Meghalaya, said. According to him, the lockdown experience would be near similar for other runners living in the neighborhood of Shillong. Run Meghalaya regularly sends runners from the state to participate in various running events in India. Some of them have been podium finishers at major races like TMM. Before lockdown set in, Gerald had set his eyes on the 2021 edition of Hong Kong 100; it has since been cancelled. Now he is toying with the idea of attending the World Mountain and Trail Running Championships due in Chiang Mai, Thailand in November 2021. Asked how Tlanding Wahlang, a regular podium finisher at marathons who has also represented India in the ultramarathon, was faring, Gerald said that he lived in a distant village where COVID-19 cases have been few so far. “ He must have been able to continue his training without too many problems,’’ Gerald said.

Karthik Anand (Photo: courtesy Karthik)

When the first phase of lockdown was announced in March 2020, Karthik Anand, who runs his own enterprise, saw his work take a dip. It gave him more free time. The Bengaluru-based runner spent the month of April and May focused on his workouts and runs. In the process, his timing efficiency in the five kilometers and the half marathon improved. “ I was able to continue running through the lockdown period. I did not face any hassles running on the roads of Bengaluru,” he said. Karthik immersed himself in training and organizing training races during these months. As a member of Pacemakers, a marathon training group based in Bengaluru, Karthik led the process of organizing runs over distances ranging from 10 km, half marathon and 32 kilometers to the marathon; he managed the logistics for these outings. These running events were held for a very small number of participants with safety protocols in place. Pacemakers held these runs in July (10 km), August (21 km) and September 2020 (32 km and the marathon). The September 2020 race helped the runners of the group who had signed up for the virtual segment of Boston Marathon 2020. The group was able to get permission from the police to organize these runs as the number of runners was small and all COVID-19 protocols such as maintaining physical distancing and avoiding contact were in place. Pacemakers plans to hold a marathon – yet again of above said containable dimension – in January 2021 coinciding with the traditional timing of India’s biggest event in running: the Tata Mumbai Marathon. It is held annually on the third Sunday of January. The January 2021 run in Bengaluru is being organized by Pacemakers, Jayanagar Jaguars and Runners 360, all city-based training groups. The run is exclusively for the members of these groups, Karthik said.

Idris Mohamed (This photo was downloaded from the runner’s Facebook page)

These have been interesting times for amateur runner Idris Mohamed, currently based in Chennai. For several years he has been a familiar face on the Indian road racing circuit, often securing podium finish in his age category. When the lockdown struck Idris was in Chennai; his family, in Thiruchirappalli. For three to four months he didn’t get to visit them. That was a trying period. He continued with his strength training and the new line of work he had commenced – coaching. It is now a bit over a year since he donned the role of a coach. He does this in two ways. He is a coach with Asics Running Club in Chennai; he also coaches on his own. The latter is proving valuable now because people have begun getting tired of online coaching. With the earlier restrictions on mobility now relaxed, it is possible for Idris to offer one on one coaching. “ When I started coaching I was a bit nervous because I was unsure if I would be able to articulate, communicate and teach as required. But now I am comfortable. I find coaching very fulfilling,’’ he said. Engaging with another person and helping him / her, shifts the focus away from oneself; it is a healthy relief in these times. Idris also operates a fitness studio in the city. Besides podium finishes on the domestic road racing circuit in pre-pandemic days, Idris was also active in the world of Masters Athletics. At the Masters Asian Championships held in Malaysia in December 2019, he secured gold medals in the 1500m, 5000m and 10,000m. Notwithstanding the expectations and the pressure to train these achievements bring, Idris felt that the lockdown offered a relevant dose of downtime. “ My aim during the lockdown and the unlock phase that followed was to do what is needed to maintain my physical fitness without getting into heavy intensity workouts and such,’’ he said. It may have affected his performance. Recently he ran the virtual TCS 10k and his timing of 42 minutes was slower than the 37 minutes he clocked at the same event in 2019. Once things are fully back to normal, Idris hopes to train as well as he used to before. He has a reason – he would like to participate in the next edition of the Masters Athletics World Championships.

Shilpi Sahu (Photo: courtesy Shilpi)

The sudden lockdown resulted in people getting stuck wherever they were. Shilpi Sahu, from Bengaluru, was held up in Kerala for seven weeks. It put a complete stop to her running. All over the country, the initial phase of lockdown was rather strict with even those out on their regular morning walk or jog sometimes accused of flouting the law. Shilpi resumed running only sometime in May; she started out with small distances. She has been running alone during these months of pandemic. “ It is quite okay to run on the road and we are able to pull the mask down as people are few early in the morning,” she said. In Bengaluru, there are some areas with open space and less crowding. The fear of contracting the disease forced many runners to stop training outdoors completely but with time they have begun venturing out, she said. Shilpi has not been participating in any of the virtual running events. “ A few of us travelled to the place where Kaveri Trail Marathon is held every year and did self-supported training runs of varying distances,’’ she said. The 2020 Kaveri Trail Marathon, a much loved event, was cancelled owing to the pandemic.

Siddesha Hanumanthappa (this photo was downloaded from the runner’s Facebook page)

When the COVID-19 lockdown was announced in March and Work from Home (WFH) commenced, Siddesha Hanumanthappa found himself with more time on his hands. A scientist by profession, he has been running regularly for the past 29 years. A break in running due to the lockdown was unacceptable for him. He realized that it would be possible to continue his running streak, if he set out early from his house. “ I would leave my house as early as 4 AM and try and finish my run by 6.30 AM,” he said. To do this, Siddesha would wake up at 2.30 AM, finish his core workouts and strengthening exercises and then embark on his day’s run. A couple of times, policemen stopped him on the road and asked why he was out. But that was it; nothing ever got out of hand. Over time, Siddesha started building up his mileage – initially it was 10km; he increased it to 15km and 20km. “ By April, I was hitting 35km daily mileage and by May I touched 38-40km,” he said. His monthly mileage which was averaging around 350-400 km in the run up to lockdown, touched 750km in April and 950km in May. By early July, his daily mileage had increased to 38-40km. “ Then somebody asked me why I was not doing a marathon,” he said. It prompted him to start running distances equivalent to a marathon (42.2km). On July 17, he ran a marathon. He sustained the trend. By December 18, he had completed 100 marathons in 2020. According to Siddesha, as of December 29, including the events he ran before lockdown like the 2020 Tata Mumbai Marathon, he had completed 104 marathons and the year’s total mileage on feet was around 11,000km. “ All my runs through the lockdown period and after the lockdown got relaxed were self-supported. Along my route in central Bengaluru there are street vendors on cycles. I stop at each of these vendors to buy water or coffee or chikki,” Siddesha said. Despite his daily running, he has not had any injuries. He attributes it to his core and strength workouts and post-run stretching. Siddesha, who has run some of the World Marathon Majors – he did Boston, New York and Chicago – has mostly stayed away from virtual runs.

Venkatesh Shivarama (Photo: Shyam G Menon)

It is difficult to filter and highlight what exactly drove bicycle sales during the pandemic because the market for bicycles straddles several price categories and each category has its uniqueness. This blog usually writes on performance cycling; it features road bikes, hybrids and mountain bikes – all slightly expensive (to genuinely expensive), mostly imported (or at least featuring imported components) and falling in the premium segment of the Indian market. Herein, the demand is said to have been fueled by the need for mobility and physical fitness, with the latter mentioned by those in the bicycle industry as perhaps the more dominant demand driver. The pandemic highlighted the importance of staying physically fit. “ We typically sell bikes priced between Rs 25,000 to Rs 100,000. When lockdown began to ease, there was a surge in demand; it was nearly ten times what we experienced in pre-pandemic days,’’ Venkatesh Shivarama, senior cyclist who also runs the Bengaluru-based bicycle retailer, Wheel Sports, said. Available stocks were lapped up by buyers and fresh stocks have been difficult to procure. There is a reason for it. The surge in demand for bicycles was worldwide and shops in several countries were exhausting their stocks. This put pressure on the entire supply chain from retailer to importer to bicycle and bicycle gear manufacturers. Adding to the strain was the fact that all these sites were also limited by the pandemic in their capacity to function properly. And even if they became fully functional, there was sufficient demand piled up to keep supplies inadequate for a while. The availability of spare parts (components) was also badly hit. Waiting lists for bikes and components materialized. Likely complicating the situation were the inherent peculiarities of the business. Bicycles in the premium bracket are truly international pieces of machinery. The aggregate is designed in one place, the frame is made in another place, the components come from still other places and the final assembly may be elsewhere. There is much shipping involved. Additionally, within the ecosystem of components manufacturing, there are names which stand head and shoulders above the rest with sizable reputation and market share to their credit. Thus a good quality chain may be sourced from a couple of reputed companies but the same cannot be said of the cassette, wherein if you want the best, the choice is limited. Getting the dominant brands (in component manufacturing) to respond quickly to demand spikes of the scale witnessed recently won’t be easy. On the other hand, expecting competing component manufacturers to step up also won’t be easy because fresh investments require a lead time to yield marketable products. Switching component suppliers is also easier said than done because there are well settled price points to meet in the market. Further, in India, some key bicycle components like good quality imported tyres have become victim of protective trade barriers. Consequently, according to Venkatesh, a range of components spanning chains to cassettes, tyres and tubes have suddenly become difficult to access. The only way out is for the market to stabilize with time. “ I am hoping that by February-March 2021, we should be in a better situation,’’ Venkatesh said.

Zarir Balliwala (Photo: Latha Venkatraman)

Among sports that were hit hardest by the lockdown, was swimming. “ It has been quite a wash out this year,’’ Zarir Balliwala, President, Greater Mumbai Amateur Aquatics Association (GMAAA), said. From the time lockdown took effect in late March, swimming pools stayed shut. While pools have since opened for competition swimmers (the central government announced it as part of Unlock 5 effective October 1; states followed but based on their risk assessment, Maharashtra allowed competition swimmers to access pools from early November), there will be a long curve to regaining the earlier levels of performance. “ There is only so much dryland work outs can do to keep swimmer in shape. Ultimately swimming needs access to water. From late March to the time competition swimmers were permitted access to water again, those into swimming have been without the medium of their sport. So it will be a long journey getting back to form. The journey to peak performance levels will likely be longer for those specializing in the sprint events,’’ Zarir said pointing out that a lot of hard work is required to shave off those seconds in timing which make a winner one. He expects that if all goes well and the next round of district, state and national level competitions get back on track, then by April 2021 some level of performance should return to the sport. There are also grey areas in the unlock format. For instance even as competition swimmers have been allowed access, it is up to the managers of a pool they approach to decide whether it makes sense to open the facility and keep it running for a small group of users. Categories like channel swimmers (endurance swimmers and open water swimmers seeking to cross straits and channels) who too benefit from access to pools, don’t qualify to be called competition swimmers. Same would be the case for triathletes as many participate in well-known competitions that are however not part of what the government normally recognizes as competitive events. As yet in these instances, the managements of pools have used their own discretion and tried to view requests sympathetically. Finally, there is the continuing absence of recreational swimmers from the frame and the question of when they will be allowed back to the pool. Zarir hopes that more clarity will be available in the first half of 2021.

Corina Van Dam, popularly known as Cocky (Photo: courtesy Cocky)

In Mumbai, Corina Van Dam (Cocky) was disappointed when Swimathon, a swimming event that was to be held towards the end of March 2020, was cancelled due the pandemic and lockdown. Cocky was slated to participate in the 10 km event. She had done all the necessary training. Soon after that, a triathlon slated to be held in April at Mahabaleshwar was also cancelled. “ I discovered the balcony in my apartment; I began seeing it in new light. I started running in the balcony; I also did some cycling. Just before the lockdown, I had bought a trainer for my cycle and that helped me cycle indoors,” she said. She also followed many of the online home workout programs put out by Mumbai Road Runners (MRR), an online community of recreational runners; she also followed other running groups and coaches including Girish Bindra. “ I do not like to do core and strength workout. But during the lockdown I did these workouts regularly and now they have become a part of my routine,” Cocky said. It was sometime in mid-July that Cocky commenced running and cycling outdoors. A recreational triathlete, she has been missing her swimming pool sessions. Pools stayed shut for long due to the pandemic and when the government decided to reopen some, it was for competition swimmers. Not one to be boxed into a corner by these limitations, of late Cocky has been doing open water swimming in the sea. Additionally, she engaged herself in a number of challenges thrown up by various running groups such as 100 days of running and Run to the Moon among others. “ Besides these, I fashioned my own challenges to keep the fitness activity going,” she said. Cocky also enrolled for the virtual race of Amsterdam Marathon. She chose a one kilometer-loop in the area where she resides and ran at night to cover the distance of 42.2 km. The cops in the area knew her well; so being out at those hours wasn’t a problem. Closer to the time of writing, she cycled from Mumbai to Malvan. “ I will continue to do some of the virtual events,” she said.

Sharath Kumar Adanur (Photo: courtesy Sharath)

At Jamshedpur, Sharath Kumar Adanur was able to continue his running through the COVID-19 lockdown. His house is within a fairly large gated community. “ I was able to run inside my housing complex in a 600 meter-loop. When the lockdown norms started to ease, I ventured out for easy runs and occasional time trials,” he said. During the peak lockdown period, he also focused on strength training. Many recreational runners have been participating in virtual running events but Sharath has not opted for these. He made an exception for a 10 km virtual run organized by Tata Steel, where he managed to get a personal best for the distance. He completed the run in 34:24 minutes, an improvement on his previous personal record of 35:32 minutes set at TCS World 10k in 2017. Sharath did the Tata Steel Virtual run at the JRD Tata Stadium. “ I wanted to get a good timing. Running on an athletics track was really good and it helped me with my timing,” he said. Sharath also did a Fast & Up 5km virtual run on a request from a friend. “ This one I did on the roads,” he said. He finished the run in 17:01 minutes. He has however stayed away from doing other virtual runs. “ I have not felt any attraction for these virtual running events,” he said. He is slated to do a physical marathon organized by running groups in Bengaluru, on January 17, 2021. Getting back to running a physical event will be a welcome change from these past few months of solitary running, Sharath said.

Dnyaneshwar Tidke (Photo: courtesy Dnyaneshwar)

Coach and runner Dnyaneshwar Tidke was completely confined to his house in Panvel during the early days of lockdown. For Dnyaneshwar, who normally runs six days a week, the confinement prompted him to work on his overall strength, agility and flexibility. He started creating videos of his workout plan for his wards at LifePacers, a marathon training group based in Navi Mumbai. “ The videos focused on whole body workouts with emphasis on stretching, flexibility, coordination and balance apart from strengthening,” he said. Alongside his role as a coach, he started to offer challenges to his team including squats, push-ups among others to keep the runners engaged and motivated. By the end of April 2020, he was able to venture out for outdoor running. “ There are many trails quite close to where I stay. I would set out early morning on my two-wheeler, park it and run on those trails,” he said. Over time, he started to build his mileage. “ I was able to work on good base-building during this period,” he said. He believes he is on an upward curve in terms of his endurance and fitness as a runner. His weekly running mileage is around 80-100 km these days. But he has largely stayed away from virtual events and has also not encouraged his team at LifePacers to pursue that route to stay motivated. The experience of a real race is something that he misses immensely. A competitive runner and an age category podium finisher, Dnyaneshwar believes real races will start in a limited way from the second half of 2021.

Seema Yadav (Photo: courtesy Seema)

For much of the lockdown period, Faridabad-based recreational runner, Seema Yadav, spent time in Bhiwadi in Rajasthan. She had landed there with her son during his school break to visit her father and with the sudden imposition of lockdown ended up being there for nearly three months. She did indoor workouts and stepped out to run when lockdown norms eased a bit. Following a brief period back in Faridabad, she returned to Bhiwadi for another month’s stay. “ I was anyway in the process of recovering from injuries. I was following the physiotherapist’s plan, which included strength training among other elements,” she said. Seema had enrolled for the Airtel Delhi Half Marathon (ADHM) virtual race but was unable to do it because of personal reasons. “ Every year, I try and get a personal best at ADHM. I wanted to finish the run in one hour and 30 minutes,” Seema said. A few days before the event, her husband had to have an emergency operation and she was forced to suspend her training as she had to juggle managing the home front, taking care of her son and staying connected with the hospital, where her husband was admitted. A doctor by training, Seema couldn’t visit the hospital due to COVID-19 restrictions; she coordinated with her husband’s doctors. “ I started training again after everything reverted to normal at home. I decided to do a virtual half marathon on December 12, 2020. I found out that there was a virtual run, Millenium City Marathon on the same day,” she said. She completed her run in 1:30:18, improving from her previous personal best of 1:34:12 set at the 2019 edition of ADHM. Seema plans to continue with her training runs, time trials and strength training. “ I may sign up for a physical race, if the number of runners is small,” she said.

Girish Bindra (Photo: courtesy Girish)

At the start of the lockdown, Mumbai-based Girish Bindra set about fashioning his own workout plans that incorporated various elements of strength training, core workout and high intensity interval training. A coach for Asics Running Club, Girish sometimes broadcasts his workouts on social media platforms for the benefit of his mentees. After the lockdown norms began to ease, he started frequenting the outdoors for his training runs. Shortly thereafter, he enrolled for the virtual London Marathon that was held in early October, 2020. His training for London Marathon was far from adequate. On the day of the run, a short heavy downpour forced him to delay the start but overall the run went off quite well in terms of support and performance. Girish has participated in a number of virtual running events this year including Comrades Marathon, Berlin Marathon, Chicago Marathon, Amsterdam Marathon, Barcelona Marathon, New York City Marathon and ADHM where he did the half marathon distance. He also did Asics Ekiden Challenge 42.2 km relay as well as a solo marathon and the 50 km category of the virtual race of Tata Ultra.

Abbas Shaikh (Photo: by arrangement)

Abbas Sheikh, recreational runner and coach from Mumbai, was confined to his house in the initial phase of the lockdown. That period was quite difficult; he even doubted whether he would be able to return to running. “ I started running in June but the mileage was quite low. I found it tough to run. Even a 10 km run would take so much time,” he said. Gradually, he was able to get back to his full-fledged training plan and coach other runners alongside. Although virtual runs became a fad during the phase of lockdown and its progressive relaxation, Abbas did not enroll for any of them. However, he did pace runner Kranti Salvi, when she did the virtual London Marathon. According to Abbas, virtual events may work as motivation but they lack the authenticity of the real event. A physical event is a composite of many live ingredients. “ I don’t see any point going for virtual runs. In any case, I run 30-40 kilometers on weekends. Every other weekend I run a marathon as part of my training,” Abbas said. His role as a coach found traction when lockdown norms started to ease in June. “ But the pick-up in interest started sometime in September and now entire families are turning up to train,” he said. Abbas works with Coach Savio D’Souza; he is part of Savio’s team. He said he has registered for an upcoming 12 hour-stadium run in the city.

Pranali Patil (Photo: courtesy Pranali)

In the initial phase of lockdown, when the quarantine centers and field hospitals for treating COVID-19 were still being set up, hospitals saw an inflow of patients affected by the virus. At the same time, fearing spread of infection, the general intake of those suffering from other diseases and approaching hospitals for treatment, reduced. In that period, Navi Mumbai-based Pranali Patil, an anesthetist by profession, saw that her free time had increased. But it meant little by way of mobility because the early phase of lockdown was also the strictest; nobody ventured out except for essentials. Pranali trains with the marathon training group, LifePacers and for the first three months of the lockdown she followed the online training sessions of her coach, Dnyaneshwar Tidke. “ I also took to skipping rather seriously,” she said. She tackled the 30-day challenge posed by her training group; Pranali’s challenge entailed running a minimum of five kilometers daily for 30 days. “ I also got into yoga during the lockdown months,” she said. At the time of writing, life had come full circle with her workload at the hospital increasing as many of the elective surgeries put on hold during the lockdown have been rescheduled to now.

Kavitha Reddy (Photo: courtesy Kavitha)

Once the lockdown took effect, it was almost 45 days of no running for Pune-based Kavitha Reddy. A frequent podium finisher at road races, she used the time to do strength training at home. She resumed running by jogging within the premises of her housing society; it yielded her a loop of around 750 meters that she would repeat. She did so for a month and then began running on the adjacent road. The loop there was smaller – about 450 meters – but it gave her the feeling of being out. Motivation was an issue in the early phase. Given there were no road races to focus on, it was a bit difficult initially to keep oneself running and training. Around late June, she began going out farther, running longer distances, mostly alone. In July she started to go beyond her immediate suburb twice or thrice a week. In the second week of July, she returned to regular training, running four to five times a week. There was no speed training or any such strenuous work out. The emphasis was on getting back to routine; she and her training group also did some time trials to get a sense of where each one’s performance level stood after the enforced break from routine caused by lockdown. Over July, August and September, they did three ten kilometer-runs (one 10k per month) and over October, November and December, three half marathons (Kavitha missed one of them). Amazingly she secured two personal bests; one each in the 10k (41:23) and the half marathon (1:30:23), the latter, an improvement over her timing at the 2020 Mumbai marathon. “ The personal bests have been an encouragement for me,’’ Kavitha said. Asked if the lack of any pressure to perform – it has been one of the side stories in running during the pandemic – contributed to the improved performance, she said it may be so. “ I hope the momentum carries forward into the approaching season of races slowly reviving,’’ she said. However she said that the return to participating in events will be gradual and based on people – including her – feeling more and more confident about the overall environment.

Himanshu Sareen (Photo: Shweta Sareen)

In Mumbai, Himanshu Sareen’s fitness regime during the early phase of the lockdown was centered on training for the virtual Boston Marathon with an aim to improve his speed. He had signed up for the Tokyo Marathon, Barcelona Marathon and Boston Marathon in 2020 but all these three events were cancelled due to the pandemic. Boston Marathon was held in the virtual format for those who had registered for the April race. In the months preceding the virtual Boston Marathon, Himanshu’s training, designed by his coach Ashok Nath, focused on two aspects – general fitness and improving speed. A sub-three hour marathon runner, Himanshu completed his virtual Boston Marathon in 2:58 hours. The virtual London Marathon was scheduled a fortnight after Boston Marathon. Himanshu had eyed it as a training run but on the day of the run, he appeared to find his momentum and pushed for a better timing. He finished the distance in 2:52, improving from his virtual Boston Marathon finish. For the virtual race of New York City Marathon that was next on the cards, he had initially planned to travel to New York for a holiday and do the run there. But with the pandemic showing no signs of ebbing, he ruled out travel and decided to run close to his place of residence. He finished the run in 2:47 hours, a personal record. “ The weather was not so good on the day I chose to run NYCM. But having done two marathons, I could capitalize on my good form to push for a personal best,” he said. Virtual runs do not offer the thrill of a real race. “ The experience of travelling to the venue, going to the expo and running through famous landmarks is absent in a virtual race,” he said. Himanshu has traveled across the world to run marathons and races of other distances. “ Virtual runs do offer some advantages. You can wake up at the time of your choice and start the run a few minutes late or early. For shorter distances, we can do multiple attempts too,” he said. Himanshu used the lockdown period to improve his time efficiency over the shorter distances such as one mile, 5 km, 10 km and half marathon. “ I have got reasonable improvement. This focus will continue,” he said.

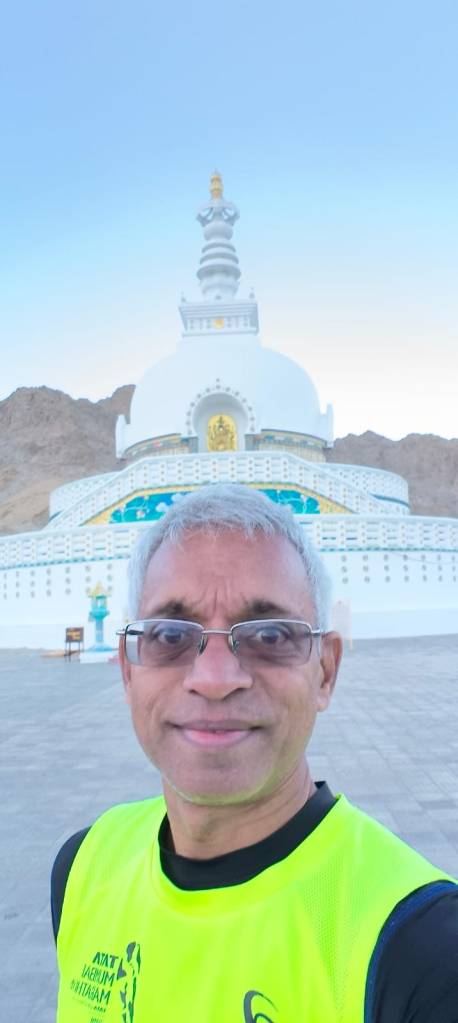

Dr Rajat Chauhan in his role as race director of La Ultra The High; this photo is from an earlier edition of the race in Ladakh, location: North Pullu near Khardung La (Photo: Shyam G Menon)

With only days left for 2020 to draw to a close, Delhi-based ultrarunner and specialist in musculo-skeletal medicine and sports and exercise medicine, Dr Rajat Chauhan, shared his take on the year, from the perspective of a healer. To begin with, the pandemic and the lockdown that followed saw a major shift in work pattern; Work from Home (WFH) became the norm. This resulted in people making do with infrastructure that wasn’t originally meant for such purpose. Some companies disbursed money for staff to upgrade work facilities at home but ultimately the alterations and improvements rarely match what an office made for work offers. Adding to this has been extended hours of work; from the earlier 8-10 hours of work, people – given they were anyway at home – were on call for 13-14 hours. The resultant chair-bound life and stress have caused an increase in aches and pains. But it is the next point Dr Chauhan mentioned that genuinely engaged. Doctors like him are usually accessed against payment of a fee. As the economy got hit by pandemic and lockdown, many people lost their jobs or witnessed salary cuts. This meant their disposable income for treating medical complaints likely shrank. There is probably a lot of people out there who aren’t reporting their health problems because they can’t afford consultation fees and treatment. It prompted Dr Chauhan to highlight the need to invest in precautionary measures and advise pushing physical limits conservatively, in his social media interactions. As he put it, the number of people running for physical fitness is likely much smaller than those doing it for mental peace and happiness. “ At some point, running becomes important because it is contributing to your mental well-being,’’ he said. Given the economic pressures and mental depression of pandemic, the existing pre-pandemic army of runners and their daily activity has been complemented by the entry of new runners jogging to beat the blues and old ones jogging more to beat the greater load of blues. Adding to this has been the emergent culture of challenges – back to back running, back to back exercises, virtual races and pressures caused by social media advertising what everyone is doing. “ On the average, the number of over-use injuries appears to have gone up,’’ Dr Chauhan said. What is overlooked in such incessant physical strain is the importance of recovery. It is during recovery time that the body adapts and gains optimal strength and stamina. When you deny the body adequate time to recover, you are pushing things downhill. And yet again, the point to remember is that courtesy salary cuts, job losses and resultant avoidance of medical intervention, we may not be seeing the complete picture. “ In the end, you say running did this to you. But it is not running that is to be blamed; it is you and how you handled running that is at fault,’’ Dr Chauhan said.

Ramesh Kanjilimadhom (Photo: courtesy Ramesh; this picture is from the New Delhi Marathon)

While several races spawned apps offering the event in virtual format and some other events debuted purely as children of the app era, not every race organizer bit the virtual-bullet. One such event that accepted cancellation of its 2020 edition in view of COVID-19 but desisted from floating an app was the Spice Coast Marathon held in Kochi. City based amateur runner and one of the founding members of the running group Soles of Cochin (they organize Spice Coast Marathon), Ramesh Kanjilimadhom put the decision in perspective. According to him, the attraction in Spice Coast Marathon is the opportunity to run in Kochi; the marathon route runs through Fort Kochi, which is home to much history and heritage. Neither that ambiance nor the enthusiasm of the organizers, supporters and the volunteers can be captured in an app. Runners know this well. “ Take for example, the Hyderabad Marathon. I personally think it is among the best in its class in India. They have a great set of volunteers. But will an app convey all that?’’ Ramesh asked. It raises the question: who wants the app the most? Very likely, the ones valuing it are the sponsors as the app offers a platform to keep events and supporting brands visible at a time when physical races are getting cancelled owing to pandemic. Apps don’t cost a lot to make. When Spice Coast decided to cancel its 2020 edition and not have an app alongside, the organizers checked with the sponsors if it was alright. “ They were cool about it,’’ Ramesh said. While he did encourage some of his friends to run virtual races of their choice, Ramesh didn’t register for any virtual event. He likes the real event and is waiting for things to settle down and the machinery of physical events to revive. His own experience of 2020 has been akin to a year of reflection and experimentation. The absence of races has infused an element of naturalness into running. There are no external goals to chase and to that extent running right now, is less synthetic. “ In the initial part of the lockdown, like everybody else, I too was indoors. When the freedom to move returned, I recommenced my running and it has progressed consistently. I used the opportunity to try slow running and heart rate running. A lot of people have changed their approach to running,’’ he said pointing out that there are others too who have used this juncture to revisit questions around why they run, what sort of running they wish to do and how to train.

The 2018 Tata Mumbai Marathon (TMM) in progress; elite contingent on the right (Photo: by arrangement)

By all accounts, the return of physical races depends on government, race organizers and participants, feeling confident. A persistent lacuna herein has been the absence of a body representing race organizers. Such a platform can be helpful in times like the present, when the multiple verticals that usually converge to enable a race have to be spoken to and their confidence in events restored. But said platform is absent. Events of some scale with pandemic protocols in place were reported from China, US and Australia in the final months of 2020. In race organizer-circles there is expectation of events capped to limited participation, happening with safety protocols in place, in the first quarter of 2021. How successful they will be is anybody’s guess. The race organizer can organize and invite but ultimately participation must manifest and that is influenced by how secure the overall situation feels. As mentioned in the introduction, the Chennai Marathon with participation capped at a maximum of 1000 runners is slated for early January and talks are on for a similar event over a shorter distance in Hyderabad later the same month. They should work as icebreakers, test cases. A recent survey of runners by one of the players in the industry indicated that prospective participants at races may be willing to pay more so that event managers can put safety protocols in place. Meanwhile, with no mass participation road races since March 2020, the industry of running saw its share of economic impact. At various related organizations, sources said, there have been instances of delayed payment of bills and salaries, layoffs and migration of skilled hands to other sectors. It is also believed that some of the marginal outfits may have given up and shifted their attention elsewhere. Before the pandemic, India was estimated to have more than 1300 road races of various dimensions being held annually. On the other hand, just as life under lockdown highlighted the importance of essentials over luxuries, the tightrope act of organizing races with safety protocols in place and not making it very expensive either, has got managers revisiting the event model to separate the essentials from the dispensable add-ons. Suddenly the focus is on what a running event actually requires – COVID-19 protocols; timing certificate, proper measurement of distance, well defined closure of roads, hydration, aid stations, medical assistance – that sort. The more superfluous items of the pre-pandemic business model seem chop-worthy. “ This is a good opportunity to recast the business model of these events and make them more relevant to running,’’ Venkatraman Pichumani of You Too Can Run, said.

(The authors, Latha Venkatraman and Shyam G Menon, are independent journalists based in Mumbai. Please note: some of the timings, mileage and number of marathons run are as said by the athletes spoken to.)