Please note: The 2014 Girivihar Climbing Competition concluded on January 26. Featured herein, are daily reports filed when the event was on. For an overview of the run up to the 2014 competition and a simple primer on how a competition works, please visit the earlier post: 2014 Girivihar Climbing Competition / Countdown.

Please note: The 2014 Girivihar Climbing Competition concluded on January 26. Featured herein, are daily reports filed when the event was on. For an overview of the run up to the 2014 competition and a simple primer on how a competition works, please visit the earlier post: 2014 Girivihar Climbing Competition / Countdown.

Day 4 / January 26: Republic Day.

Last day of the 2014 competition when the wall would be open for the public to climb.

I reached Belapur, late afternoon.

The public had come, climbed and gone.

It was wind-up hour.

The beautiful orange wall was being taken down, starting with the climbing holds.

Some of those who had participated in the Master’s round helped, among them – Gaurav Kumar, Madhu C.R, Manikandan and Sandeep Maity. As the crash pads were taken off the ground and stacked in a pile, three young boys ran in to climb the stack and sit on its heaving surface. Nine year old-Rajbeer Singh sat atop it still wearing the gold medal he had just received at the nearby stadium for winning a 200 metre-race. Bhangra music from the stadium wafted in. A portion of the climbing competition’s venue had been taken over by a group playing cricket. In India, that game is like the sea at a beach. Other sports and games live in the land revealed between a wave receding and another rolling in. The climbing competition’s time was up.

Some of those who had participated in the Master’s round helped, among them – Gaurav Kumar, Madhu C.R, Manikandan and Sandeep Maity. As the crash pads were taken off the ground and stacked in a pile, three young boys ran in to climb the stack and sit on its heaving surface. Nine year old-Rajbeer Singh sat atop it still wearing the gold medal he had just received at the nearby stadium for winning a 200 metre-race. Bhangra music from the stadium wafted in. A portion of the climbing competition’s venue had been taken over by a group playing cricket. In India, that game is like the sea at a beach. Other sports and games live in the land revealed between a wave receding and another rolling in. The climbing competition’s time was up.

Sandeep Bhagyawant brought a box of ice cream. It was relief for those working to dismantle the wall in the hot sun. Freelance journalist also got one. In Mumbai and Navi Mumbai, winter has become a flash in the pan. Welcome to warm January. There was something touching about the scene before me – devotees of a fringe sport, club members and volunteers who had sweated it out to hold a climbing competition, now dismantling just what they laboured to assemble. The orange wall developed gaps like knocked out teeth, as panels were taken off.

Sandeep Bhagyawant brought a box of ice cream. It was relief for those working to dismantle the wall in the hot sun. Freelance journalist also got one. In Mumbai and Navi Mumbai, winter has become a flash in the pan. Welcome to warm January. There was something touching about the scene before me – devotees of a fringe sport, club members and volunteers who had sweated it out to hold a climbing competition, now dismantling just what they laboured to assemble. The orange wall developed gaps like knocked out teeth, as panels were taken off.

Franco Linhares, former president of Girivihar, was there helping with the day’s work. I asked him what he thought of the just ended eleventh edition of the event. “ This is the best wall we have built so far. We also had a greater variety of holds and features to work with,’’ he said. The quality of Indian climbers in the men’s category has improved. Although there is still much distance between the best of Indian sport climbers and those from elsewhere in Asia, they have become stronger. “ But there is a lot of catching up to do in the women’s category,’’ Franco said.

Franco Linhares, former president of Girivihar, was there helping with the day’s work. I asked him what he thought of the just ended eleventh edition of the event. “ This is the best wall we have built so far. We also had a greater variety of holds and features to work with,’’ he said. The quality of Indian climbers in the men’s category has improved. Although there is still much distance between the best of Indian sport climbers and those from elsewhere in Asia, they have become stronger. “ But there is a lot of catching up to do in the women’s category,’’ Franco said.

It is now night.

As I write this, the arc lights may have been switched on at site in Belapur to help the team finish their wind-up work.

Except this time, there wouldn’t be an orange wall shining bright centre stage.

Thank you for looking up all the posts regarding the just ended competition, from countdown to daily reports.

I dedicate the posts to a beautiful orange wall.

Day 3 / January 25: After the Master’s round of the annual Girivihar climbing competition concluded on Friday (January 24), it was the turn of the amateurs.

Day 3 / January 25: After the Master’s round of the annual Girivihar climbing competition concluded on Friday (January 24), it was the turn of the amateurs.

Results (in order of first, second and third):

Men

Dhawal Sharma, Bhupesh Patil, Varad Desai

Women

Shimul Bijoor (this category had one winner as only one person finished a boulder problem).

Boys

Ojas Marathe, Vishal Gaikwad, Akash Gaikwad

Junior Boys

Vinay Gaikwad, Omkar Adhav, Rutoo Pendse & Rutik Marane

Shreya Nankar, Nirmalika Pandey, Sania Nargunde

The mood at the venue was more relaxed and playful today given the large number of school children around. Many of the seniors who had competed in the Masters’ category stayed on to cheer the amateurs and help in route setting.

The competition’s Chief Route Setter Vaibhav Mehta spared time to talk to this blog. According to him, in the Masters’ category, the 2014 edition of the event saw boulder problems ranging in difficulty from 6b+ to 7c+ for men and from 5c to 6c for women. Over the years, the grades have been rising. “ The competition is getting better every year. There has been much improvement in the calibre of Indian participation,’’ Vaibhav said. As mentioned in the report of January 24, when the men’s competition in the Masters’ round, reached semi final stage, some of the promising Indian climbers got eliminated or barely scraped through to the final. Anything can happen in competitions. Still, in the run up to the event, there had been much expectation from a bunch of youngsters who recently broke through grades in sport climbing, considered very tough for Indians. Quite a few of these climbers were present at the 2014 competition. Singapore’s Adriel Choo handled their challenge well in the semi final and calmly proceeded to win the final, successfully defending his title. I asked Vaibhav, one of the finest sport climbers around when he was based in Mumbai and active in the climbing scene here, what he thought of Adriel.

The competition’s Chief Route Setter Vaibhav Mehta spared time to talk to this blog. According to him, in the Masters’ category, the 2014 edition of the event saw boulder problems ranging in difficulty from 6b+ to 7c+ for men and from 5c to 6c for women. Over the years, the grades have been rising. “ The competition is getting better every year. There has been much improvement in the calibre of Indian participation,’’ Vaibhav said. As mentioned in the report of January 24, when the men’s competition in the Masters’ round, reached semi final stage, some of the promising Indian climbers got eliminated or barely scraped through to the final. Anything can happen in competitions. Still, in the run up to the event, there had been much expectation from a bunch of youngsters who recently broke through grades in sport climbing, considered very tough for Indians. Quite a few of these climbers were present at the 2014 competition. Singapore’s Adriel Choo handled their challenge well in the semi final and calmly proceeded to win the final, successfully defending his title. I asked Vaibhav, one of the finest sport climbers around when he was based in Mumbai and active in the climbing scene here, what he thought of Adriel.

“ He handled the pressure very well,’’ Vaibhav said, adding that the Singapore climber seemed rich in exposure to competitions. He was experienced and comfortable with the format. Some things about Adriel genuinely impressed. For instance, irrespective of how his fortunes were with a particular boulder problem, he didn’t carry its legacy over to the next one. He approached every problem with a fresh mind. Adriel also came across as a technically competent climber with strong route-reading ability. But what endeared him to Belapur’s climbing community and the audience at the competition, was his humility. Once he finished climbing all the boulder problems in the final, Adriel bowed to the audience which had consistently cheered him. “ An audience like the one we get at Belapur, comes to see good climbing. Adriel gave them that, plus he bowed to the audience to express gratitude for their support,’’ Vaibhav said. This combination, he felt, was something Indian climbers should notice, not to mention – the said quality and others cited previously, seemed to be there in all the participants from Singapore, pointing to a general standard in the team.

While Adriel repeated his triumph in the men’s category, his team mates Janet Goh and Lynette Koh took first and second place respectively in the women’s category of the Masters’ round.

Day 2 / January 24: The team from Singapore swept top honours on the second day of the eleventh edition of the annual Girivihar climbing competition.

Last year’s winner Adriel Choo successfully defended his title in the men’s category while team mates, Janet Goh and Lynette Koh, placed first and second in the women’s category.

Tuhin Satarkar (Pune) and Michael Schreiber (Germany) finished second and third in the men’s category, while Neha Prakash (Bangalore) took third position in women’s.

Some of the Indian climbers who looked strong and promising in the first round of the men’s category on Thursday (January 23), faded in the tough semi final. Also exiting in the semi final held today afternoon, was the team from Iran and two climbers from the Singapore contingent. The top five from the first round – Sandeep Maity, Ajij Shaikh, Tuhin Satarkar, Adriel Choo and Vicky Bhalerao, plus Michael Schreiber, made it all the way to the final. But from the semi final onward, Adriel Choo was a changed climber, increasingly showing the ability for calm, clinical execution of well planned climb, at every boulder problem. Tuhin Satarkar – he recently became the first Indian to climb an 8b+ sport route – and Michael Schreiber, kept the competition close particularly for second and third positions.

Similar systematic build up to peak performance graced the two winners from Singapore in the women’s category. In the final, Janet Goh was superb on the wall, while Lynette Koh followed closely, stronger perhaps in terms of daring but eventually limited by her smaller size. The list of finalists in the women’s category also included Siddhi Manerikar (Mumbai), Vicki Mayes (UK) and Shantirani Devi (Bangalore).

At programme’s close, prizes were distributed. With this, the Masters’ segment of the competition has concluded.

Tomorrow (January 25) there will be competitions in the amateur category. On January 26, the wall will be open for the public to try their hand at climbing. There will be a workshop on climbing for citizens.

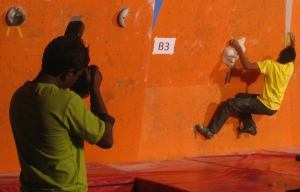

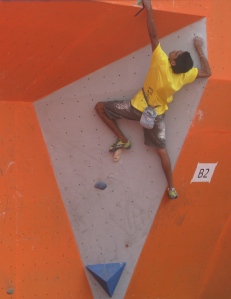

Photos from Day 2:

Day 1 / January 23: There were winners on the very first day of the eleventh edition of Girivihar’s annual climbing competition.

Adarsh Singh from Delhi emerged first in the boys’ category. Akash Gaikwad and Sachin Ahire, both from Mumbai, placed second and third respectively. This category had only one round owing to limited turn out in that age group. Still the quality of climbing on display was impressive.

Earlier today morning, the open competition, organized by Girivihar, Mumbai’s oldest mountaineering club, had kicked off with little ceremony and much action. There wasn’t any formal inauguration. After breakfast, registration and final touches to the venue – including getting all the crash pads properly arranged on the ground – the Master’s category of the event got underway.

There were thirty six participants for the first round in that category.

The Indian line-up was strong, with not just a national champion and others who had placed high in the nationals, but an array of climbers fresh from cracking some of the toughest boulder problems and sport routes on natural rock in the country. This contingent left its mark on the list of those qualifying for the semi final. Given below are the names of those going through to the next round:

Sandeep Maity (Delhi), Ajij Shaikh (Pune), Tuhin Satarkar (Pune), Adriel Choo (Singapore), Vicky Bhalerao (Pune), Somnath Shinde (Pune), Mohammad Ashraf (Singapore), Ranjit Shinde (Pune), Ryan Yeo Hong (Singapore), Hossein Mahani (Iran), Rohit Vartak (Pune), Guarav Kumar (Delhi), Michael Schreiber (Germany), Nevin Rajen (Singapore), Sidharth Adhav (Pune), Muhindra Lamabam (Manipur), Swapnil Bandal (Mumbai), Hosseini Mehdi (Iran), Prathamesh Sangale (Mumbai) and Indranil Khurungale (Pune).

Semi final and final across both categories – men and women – will happen tomorrow (January 24). Competition in the women’s category begins with semi final. Such decision – whether contest should begin with an opening round, semi final or straight with final (as happened in case of boys) – is based on the number of participants registering for each category. This year, the Master’s category – basically those who have climbed previously at national level or have proven climbing experience with grades (measure of difficulty on given route) to match – received good participation.

Semi final and final across both categories – men and women – will happen tomorrow (January 24). Competition in the women’s category begins with semi final. Such decision – whether contest should begin with an opening round, semi final or straight with final (as happened in case of boys) – is based on the number of participants registering for each category. This year, the Master’s category – basically those who have climbed previously at national level or have proven climbing experience with grades (measure of difficulty on given route) to match – received good participation.

Although begun on natural rock and spanning both bouldering and lead climbing, the Girivihar competition now restricts itself to bouldering with competitors attempting to solve boulder problems on an artificial climbing wall.

At the end of boys final, which was the last item today, the wall was opened up for half an hour, for everyone to climb. At one go, almost the entire audience shifted to the wall and were seen having a wonderful time climbing. That also tells you something about the world of climbing in India. It is a relatively small group of people, passionate about climbing and typically at events, both participant and audience.

Photos from Day 1:

Audience:

(The author, Shyam G Menon, is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai. All the photos used in these reports were taken by him.)