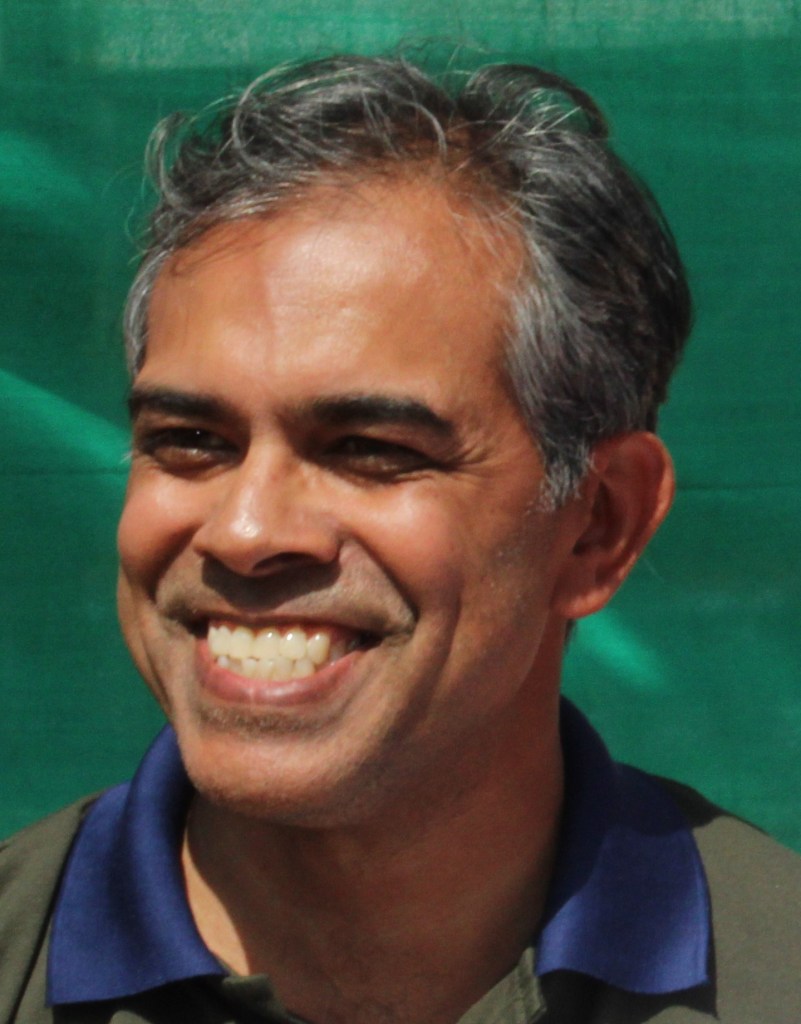

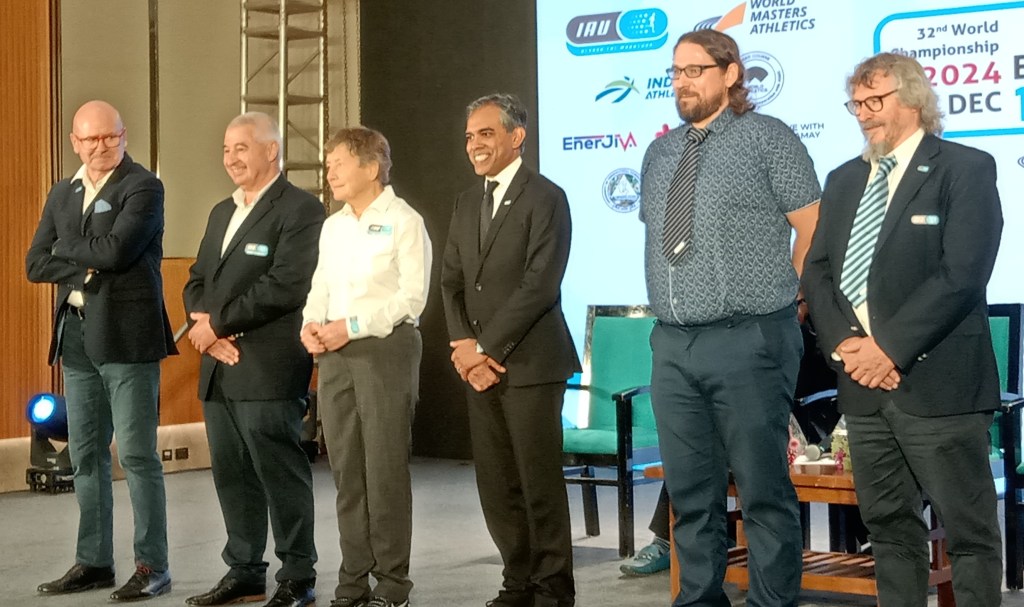

At the 2024 IAU 100 KM World Championship held in Bengaluru in December, president of the International Association of Ultrarunners (IAU), Dr Nadeem Khan, spared some time to talk to this blog. Excerpts from the conversation:

Where do things stand as far as ultrarunning events in India go?

Events in India are definitely going ahead. NEB Sports is doing an amazing job with these races. Ultrarunning has gotten better and athletes are growing in numbers and doing very well on the international stage. It is exciting to see the growth of the sport in India. Today (December 7, 2024) is a prime example. The organization of the race is near perfect. Athletes are enjoying themselves.

On the progression towards including ultrarunning as an Olympic sport what is the current status? Is it being pursued?

As an organization IAU has agreed to the fact that if anything from the world of ultrarunning makes it to the Olympics it will be trail running. This is something we mentioned two years ago. That hasn’t changed. What has changed is that the community of trail running has got a lot stronger. We partnered with ITRA, WMRA (World Mountain Running Association) and World Athletics to organize the World Mountain and Trail Running Championships. It is very exciting. It is a championship in a whole different world altogether – multiple events in very scenic locations. One was held in Thailand, another in Innsbruck, Austria and we will be holding one in Canfranc in Spain next year. There is a lot of work being done on trail running to ensure that it becomes a sport that is watched and participated in across the globe. There are a lot of discussions happening but nothing formal yet.

What kind of distances are being considered for trail running?

Nothing has been decided. The trick is to have a proposal that is attractive enough to make it to the Olympics.

You are currently at the 100 km world championships. The 50 km is very close to the marathon. When a person looks at the Olympics logically there is no reason why any of these distances or durations shouldn’t make it to the Olympics because you have stadiums and venues to run a 24-hour race and there are events like the decathlon which go on for two days. How did discussions on ultrarunning distances pan out and how did trail running emerge as a choice?

If you look at decathlon, for instance, each of the 10 events within the decathlon lasts for a much shorter period of time and not for two days. A lot of the Olympic events are decided on the basis of how attractive they are on television. When it comes to trail running, the scenic atmosphere where the races are held, may adapt well to television broadcast. The 24-hour run is an amazing event. I used to do it. But when it comes to broadcasting these events, trail running makes sense. We have tried to push the 100 km and the 24-hour races for consideration at the Olympics but we did not get a positive response. In the opinion of some of our partners, trail running might be the best bet.

In spaces like the 100 km and the 24-hour events what is IAU doing to make them globally watched as a sport which may make it to the Olympics?

We are doing that via these world championships that we keep organizing across the globe. We are giving 40 odd countries opportunities on the international stage. That in itself is a positive direction. The next step would be to increase the caliber of athletes and step up the caliber of organization of these events. A multi-faceted approach is needed from all different directions.

What are the key points in stepping up the caliber of athletes?

India is a good example. Many Indian runners are making it to the podium now in international races. It is quite exciting to see that. We have seen huge improvement in the level of athletes whenever we bring the championships to the country they belong. For instance, when athletes bring home a medal the Athletics Federation of India (AFI), now called Indian Athletics, takes notice. AFI has been a huge support to ultrarunning here. By providing an international stage, we are also contributing to the growth of the sport locally and domestically. The flip side is that we cannot just host a championship and then walk away. We need to ensure that the development of the sport continues beyond the championships. Having these championships is the catalyst for further growth of the sport. The other side of the story is to have support from athletic federations of many countries. The more the number of federations, it means greater presence of ultrarunning in those countries. It is a multi-pronged approach. This year I travelled to many countries, promoting the sport, talking to federation heads and in the process hoping to get a lot more countries to participate in ultrarunning events as we move forward.

In terms of geographies where would IAU take the championships to? Would Asia and Africa be the new geographies you would look at?

We choose the best bids, whoever offers the best bid. We are also cognizant of the fact that we cannot organize in just one continent, whether it is Asia or Europe or America. We have to go everywhere. It just happened that we got the best bids from Asia. If not the global championships it will be the continental championships.

In other sports such as sport climbing there were a series of world cups that culminated into a world championships? Is there anything similar thought about to keep the calendar of ultrarunning busy?

Ultrarunning needs a huge recovery time. Also, the clientele is different. Very few of the ultrarunners are professional runners. Many of them work for a living. They may be doctors, engineers, teachers, business people. They have day jobs that they have to go back to once the race is over. Travelling around the world to attend these races will be difficult for them. We used to have something called a 50K World Trophy Final. We used to host 50K championships in 20 countries and the leading finishers of these would get invited to run the World Trophy Final. We used to have two 50K World Trophy events but these were individually driven and not Federation driven. We converted the 50K World Trophy to a 50K World Championships. Eventually, our goal is to bring everything under the umbrella of a championship.

(The authors, Latha Venkatraman and Shyam G Menon, are independent journalists based in Mumbai)