There’s a graph in Savio D’ Souza’s phone, which has become a milestone of sorts. It depicts his progression during the half marathon, held as part of the 2025 Tata Mumbai Marathon (TMM). Among India’s top marathoners years ago and post-retirement one of Mumbai’s most sought-after coaches in long distance running, Savio finished the 21 kilometre-race in two hours, 28 minutes and 17 seconds. It’s not an exceptional timing. But it is special, for 2025 TMM marked Savio’s return to participating in the city’s annual marathon after a gap of two years enduring an unexpected downturn in health.

A physically fit individual, managing two coaching sessions every day and training and running alongside his wards for his own fitness, Savio was diagnosed with colon cancer in December 2022. The onset of discomfort and the diagnosis were not much apart. The initial symptoms included fever and discomfort in the abdominal area. It appeared to go away with a round of antibiotics. But when the discomfort returned, Savio promptly sought comprehensive medical investigation, following which, cancer was detected. The disease was locally advanced; in other words, stage three. It wasn’t just his colon, the bladder and the prostate gland were also affected. The diagnosis left Savio puzzled at start, for he was a physically active person with a longstanding track record in athletics and who in addition, neither smoked nor drank. Further, if meat consumption was cited as potential cause, he couldn’t help but notice that those into a vegetarian diet also seemed to develop the disease. “ I couldn’t figure out why I got cancer,’’ he said. On the bright side, likely due to his physically active lifestyle, Savio didn’t have any comorbidities.

Following the diagnosis, Savio resolved to follow whatever his doctors advised. He temporarily handed over the training responsibilities for his group of runners – Savio Stars (the group was commenced in 2005, the second year of the Mumbai marathon) – to Dev Raman, a senior runner. Raman was assisted by Savio’s deputies. That done, Savio embraced medical treatment. In all, Savio had 12 sessions of chemotherapy and five of radiation. The main hospital involved in treating him was Mumbai’s Tata Memorial Hospital, reputed for its cancer care. For six of the chemotherapy sessions, Savio visited Sir HN Reliance Foundation Hospital and Research Centre as well. Asked if he experienced any weakness during the period of chemotherapy, Savio said that aside from occasional blisters in the mouth, he was generally okay. He didn’t feel particularly tired or drained out. For both accessing medical care and staying positive through the treatment phase, the running community and in particular, Savio Stars, were of considerable help. In Mumbai, the typical running ecosystem featuring a large group of runners under a coach, is a small cross section of life’s essentials. Doctors who are into running were always at hand to help Savio understand test results, treatment protocols and recommend the best options in health care.

When battling cancer, a positive frame of mind is very important. Chemotherapy and radiation have the tendency of lowering the body’s capacity to defend against infections. Savio was instructed to stay off crowded places. He diligently maintained this approach for the first round of chemotherapy. Rose, Savio’s wife, used to the athlete’s ways, realized that keeping Savio indoors for long would dampen his spirits. So, on some days, his trainees out on their morning run would come by and Savio would go with a few of them to a secluded corner of the beach that was devoid of crowds, for a brief walk. He wore a mask. On July 6, 2023, after nine sessions of chemotherapy were completed, Savio underwent surgery. A part of the colon and the whole bladder, were removed. Post-surgery, the doctors had special plastic bags attached externally to his body, which collected the body’s solid and liquid waste products. He spent 13 days in hospital for the surgery. Recovery wasn’t exactly a simple path. There was a procedure endured later, in March 2024, to remove the plastic bag for solid waste, reverse that temporary method for waste evacuation and restore the patient’s ability to use the toilet. Given Savio’s bladder has been removed, the plastic bag for collecting urine will remain a permanent adjunct.

There were two moments of anxiety in the recuperation phase. Once, a block developed in the waste evacuation process causing acute discomfort. It brought Savio back to hospital briefly. The other moment of anxiety has a backdrop in physical activity to it. During these months of tackling cancer and recovering from it, Savio had his cataract operations also done. Towards the end of August 2024, he commenced a slow return to his coaching activity. He was very cautious; there was the post-surgery (cancer surgery) care to be cognisant of and cataract procedure recently done meant his eyes too had to be shielded from Mumbai’s rain. There was no more of that old Savio trait of showing his wards how to do their training. Instead, he would be present for the training sessions to oversee them and also use the time he had on the city’s Marine Drive to first walk slowly and then progressively intersperse those walks with short blends of walking and jogging. Once during this phase, he developed a small niggle in his lower back and resorting to old habit, he used a foam roller at home to address it. Not long thereafter, he found traces of blood in his urine. The doctors have since told him to completely stay off any such movements or any exercise that may strain his abdominal area (so, no planks for this runner). Meanwhile, at his training sessions on Marine Drive, which he attended in the morning (at the time of writing, Savio hadn’t yet begun attending the evening sessions), the coach kept gently nudging up the share of those run-walk blends in his walking. As he put it, even in pre-cancer days, he was always one recommending a gradual ramping up of training for his wards. “ I believe in taking things slow. Many amateur runners, when they enlist for training with me, are revisiting running after a long gap. Some of them haven’t run for years. Ramping up fast causes needless injury. Therefore, in the early stages of training, I tell them to come for the training sessions and simply walk. After all, serious training makes sense only if your body is first acquainted to those early morning hours,’’ Savio said. Post cancer, that gradual easing into running became the coach’s advice to his own self.

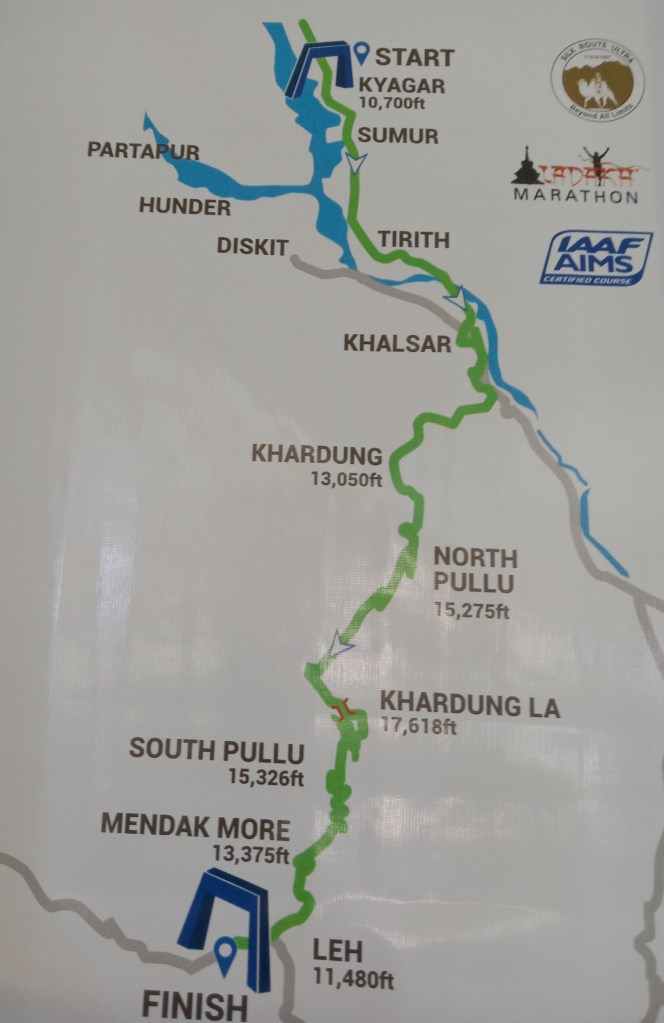

For this author, untutored in medicine, the conversation with Savio left a couple of points to reflect on. The first was the late detection of cancer. Is it a pattern seen in physically fit people that their fitness, general robustness and higher tolerance of pain, delays detection of things gone wrong? And if late detection is a trend, then would periodic medical check-ups be the relevant way forward for the physical fit? The second question was an often posed one – if diseases can set in despite investment in physical fitness, then what exactly is the benefit of trying to be physically fit? This blog met Dr Rajat Chauhan for the first time in August 2011, at the second edition of La Ultra The High, the iconic ultramarathon, once held every year in Ladakh. A specialist in sports and exercise medicine, he is also a columnist, a longstanding ultrarunner and the founder-race director of La Ultra The High. According to Dr Chauhan, there is no one-size-fits-all template or paradigm to answer the first question. To begin with the whole question of why somebody gets a disease is explicable to some extent and a grey area to some extent. A popular example would be the condition of having fatty liver disease. There was a time when it was associated with alcoholics. Now it is seen as a lifestyle disease affecting more those who don’t consume alcohol. Similarly, within the realm of certain body types generally spoken of as linked to improved well-being, smaller details count. For instance, an overweight but physically active person may be better off than a thin, physically inactive sort. In other words, merely because one is thin, one needn’t be healthier. Viewed so, there is a lot in health that is specific to the individual. Assigning general parameters could be misleading. As for detection – as much as a superior level of physical fitness may be argued to delay detection of diseases in the physically fit, it is equally possible that given individuals who exercise regularly or live the physically active life, have a better connection to their body, they may report anomalies earlier.

Specifically on colon cancer, Dr Chauhan pointed out that it isn’t usually among conditions detected early. The best bet we have against cancer at large is a good quality of life; sleeping well, preserving good mental health, having good eating habits and remaining physically active would be among the ingredients going into it. The problem with periodic health check-ups for the physically active as a general precaution to avoid late detection of diseases is that many of the diseases and conditions which visit us, typically require a detailed medical examination to show up. In other words, a general medical check-up needn’t guarantee all problems showing up. Under the system of healthcare currently available, medical check-ups are expensive. So, if one establishes periodic check-ups as the main relevant alternative for the physically fit to avoid late detection, then it could well end up as money spent to keep the healthcare system healthy rather than oneself healthy. Or consider for example, tests around joint health and mobility conducted on all who have reported for a marathon. “ Investigations like MRI done for the spine and knee, done on most of the runners as well as non-runners, would show abnormalities. Out of which, 90 per cent or more would have no symptoms whatsoever. But based on those findings, they could either be told by my colleagues that they should stop running, or their well-meaning family and friends could tell them the same too. Also, if there is back or knee pain, we need to address it smartly, when their sense of both mental and physical well-being, is rooted in running. What counts more – is it that well-being and joints still usable because of activity, or a cessation of the activity that they are in love with? Most runners, and even other sport enthusiasts end up coming to me because their other doctors have told them to stop playing the sport that defines them. It’s like a death sentence for them,” Dr Chauhan wrote in (this blog’s interaction with him was via a mix of telephonic conversation and email). Having said that, some basic medical evaluation done periodically does make sense for a general idea of where one stands.

With regard to the relevance of investing in physical fitness amidst ailments happening to even the physically fit, Dr Chauhan agreed that one of the benefits of a physically active lifestyle is reduced comorbidities. He recalled an extensive study done during the COVID-19 period in New York, which showed that those into a physically active lifestyle diagnosed with COVID-19, had milder infection or spent less time in the hospital to recover. And yet, despite the availability of such bullet points to underscore the relevance of being physically active, the most tangible justification for physical activity is that it makes people feel good about themselves in the time they are alive. On a philosophic note, Dr Chauhan admitted to wondering – “ why don’t we focus on adding more life to years than only thinking about adding years to life at any cost?’’

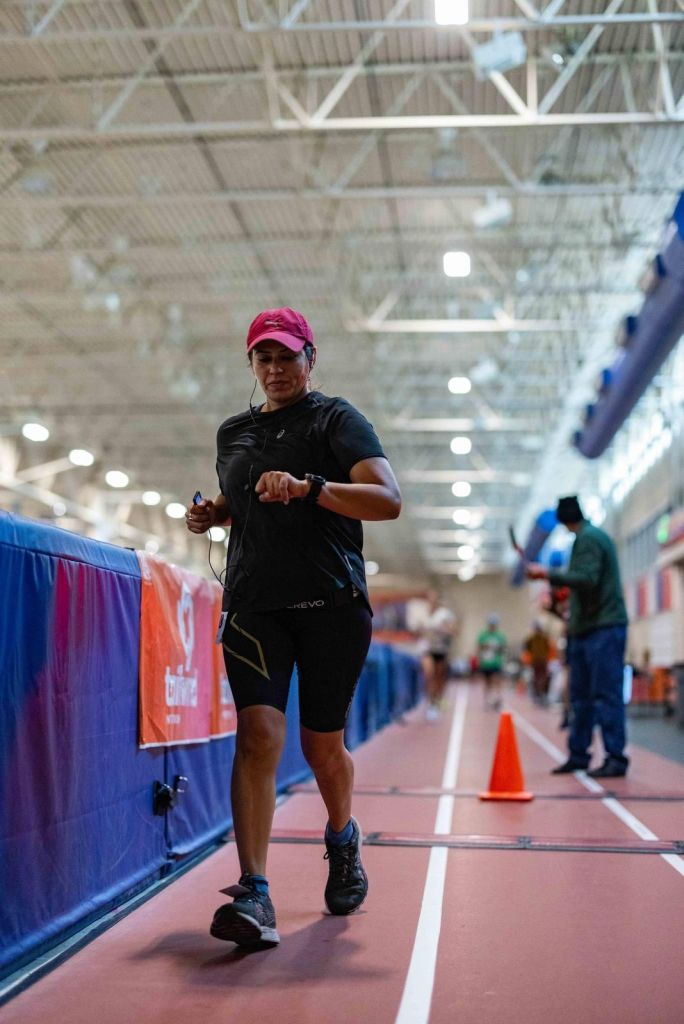

Back on Marine Drive, as 2024 entered its final months, Savio tested his post-operation fitness patiently through several days of walking and doing that blend of walking and running. Thanks to two years without any significant physical activity, there was a slump in cardiovascular fitness to overcome. As well as get them limbs moving smoothly like before. Eventually, the 71-year-old sensed his body sending a green signal for the idea he had in mind – take part in Mumbai’s annual marathon. In November 2024, Savio decided to register for the 2025 TMM in the half marathon category. The event’s organizers accommodated the late request from one of the city’s most loved coaches. Savio’s long runs in the run up to the half marathon of January 19, 2025, were just two – both of 10 kilometres each. He deemed that enough for he had been doing regular run-walk of shorter distances, had loads of experience in running from the past to dig into and his immediate goal was anyway to just complete the race. In his pre-cancer days, he was used to running long without much hydration. Post surgery, the doctors had told him to hydrate properly including at TMM. Missing a bladder, he would be running with that plastic bag meant to collect urine as it formed. “ The only issue was whether the plastic bag may flap around as I run. But that never happened during the race because I have a smooth, running style. One that doesn’t disturb the bag. And if at all the bag gets moved around, I can tuck it under the elastic of my shorts; it stays in place. Besides, every time I visited a loo along the marathon’s course, I was quicker than the average runner at finishing my business and coming off. I just have to empty my bag!’’ Savio said laughing.

Five days after 2025 TMM, at their apartment near Mumbai’s Metro cinema, Savio and Rose were a picture of happiness as they shared that graph. As mentioned, the time taken to finish was 2:28:17. Savio placed tenth out of 67 runners in his age category of 70 years and above for men. What made him love the graph, was the pattern of progression. Till around 6.5 kilometres in the race, it shows him maintaining a steady pace of seven minutes and 20 seconds to cover a kilometre. Then, over the next 10 kilometres, he turns up the pace, not ascending to dramatically high levels, but a comfortable peak of seven minutes. After that, it gently eases to a finish at around seven minutes and five seconds. In other words, tiny increments held steadily for long. “ You understood?’’ Savio asked me. I didn’t, initially. “ No, he didn’t,’’ Rose said from the side. The coach explained it again, patiently. I got it.

(The author, Shyam G Menon, is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai)