On September 8, 2023, Amit Gulia achieved the first sub-17-hour finish by a non-Ladakhi runner in the 122-kilometre Silk Route Ultra. Here’s a look into the approach he adopted for the race at altitude.

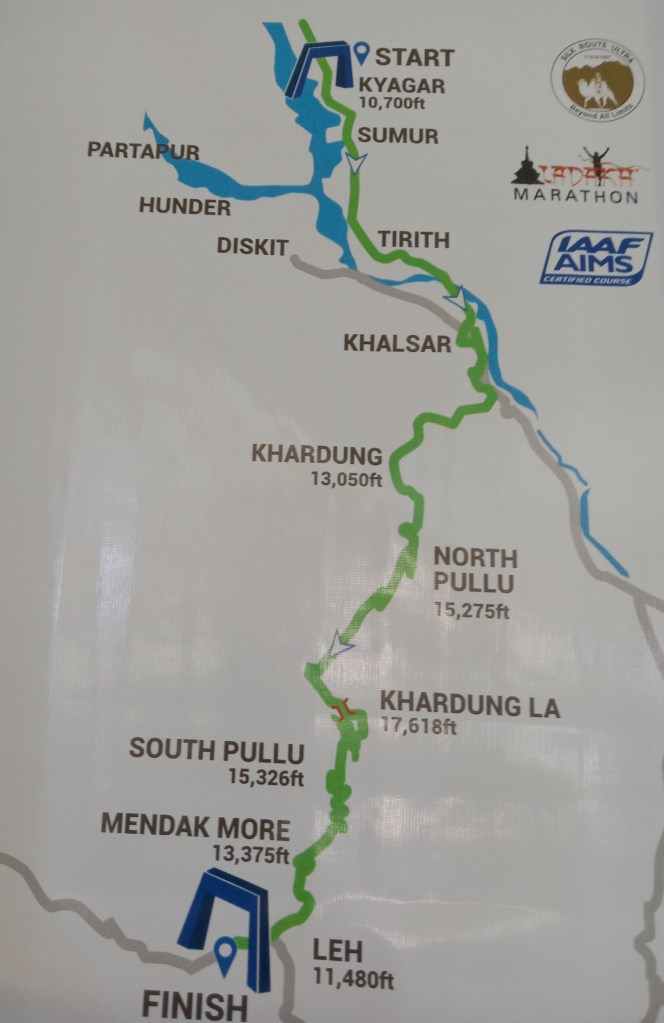

On the morning of September 8, 2023, much before the winner of the year’s Silk Route Ultra (SRU) crossed the finish line, another runner had completed the race. He would settle for fourth place as he belonged to the first batch of runners that set off the previous evening to tackle the 122-kilometre distance from Kyagar to Leh, up and over the 17,618 feet high-Khardung La. Judged by net timing, the Ladakhi runners of the second batch were faster. They would sweep the podium; first, second and third. Still, Amit Gulia’s timing was no small achievement. The 16 hours, 21 minutes and 25 seconds he took to place fourth was the first sub-17-hour finish in the race by a non-Ladakhi. In the ecosystem of the Ladakh Marathon, an event with altitude as its biggest challenge, non-Ladakhi runners are the outsiders taking the brunt of elevation.

Amit’s journey to that September finish had commenced five years earlier. Based in Chandigarh, Amit, 40, has a background in medical research He is a medical writer and since the past one year, he is also chief coach at Skechers Go Run club in Chandigarh. A runner since the age of 32-33, he has never run a marathon officially. He did so in training and the one thing he liked to do as runner, was to run long distances. That was how his drift to the ultramarathon happened. He found himself completing a marathon in training with others and still having room for more mileage. His first ultra was the popular event at Bhatti Lakes; a pucca start to his innings.

Thanks to their long distances, ultramarathons demand preparation, strategy and support. When Amit attempts races requiring support crew, that role is typically taken up by two people close to him. There is his wife Gurjeet Kaur, who like Amit, is a runner and a medical researcher. She takes much interest in his running. Then there is Vijay Pande, an engineer and runner based in Bengaluru, who Amit often consults to devise approach and strategy for the projects he undertakes. The two had met at a past edition of the Mashobra Ultra, which was among Amit’s first official forays into distances exceeding the length of a marathon. It was Vijay who introduced Amit to training with the altitude mask.

A December 2022 article by Ashley Mateo in Runner’s World explains what the altitude / elevation mask does. How it works is very different from training at altitude. When one trains at altitude, there is increased production of a hormone called erythropoietin (or EPO). It triggers the body to produce more red blood cells and form new blood vessels. This enables the body to deliver more oxygen to the muscles which in turn means faster and more efficient running, particularly when one returns to sea level. Altitude masks have valves or vents that regulate air intake. They can alter the quantity of air getting in but they don’t affect the mix of gases in the air inhaled. Consequently, when used while training at low altitude, one does not get the same benefits as when training at elevation. It is not an exactly similar situation. However, restricting the air intake contributes to something called inspiratory muscle training. It increases the strength of the respiratory muscles which can eventually translate to the ability to bring more air into one’s lungs. That’s potentially more oxygen that can get into the bloodstream. More oxygen in the muscles means one finding it easier to exercise. In other words, the mask-route is not precisely the same as training at altitude but it has an oblique benefit by way of strengthening the respiratory muscles.

Amit’s use of the device started during his preparations for the 2017 edition of La Ultra The High, an event with a basket of ultramarathons happening in Ladakh. Initially, the mask was difficult to use. But given the event he had signed up for, Amit had no other option; he persevered. That year, he won the 222 km-category of La Ultra The High, the first Indian to do so (archived results of the event show the winner’s timing as 38 hours, 20 minutes). It was Amit’s first ultramarathon at altitude; the route of the 222 km-race touched both Khardung La and Wari La (over 17,400 feet high). The template for acclimatization he fashioned for that race, has remained thereafter his rule book for races in Ladakh. Besides regular training at low altitude and the use of the altitude mask for some of the sessions therein, the other noteworthy aspect was Amit’s protocol for pre-race days in Leh. Unlike the typically anxious participants of these races who continue running at elevation or make last minute dashes to high altitude in a bid to get familiar with the environment, Amit focused on rest. In the fortnight he reserved for acclimatization before the 2017 La Ultra The High, he rested in Leh and walked around locally. There weren’t any runs, car or bike trips to still higher altitude as preparation for the race and its high passes. What is generally overlooked in such cases is that for people coming to high altitude from the outside, post-exercise recovery and healing in activities done during the acclimatization period, misses the richer oxygen levels of lower elevation. “ In my opinion, visits to high altitude and exerting oneself during the acclimatization phase before a race, inflicts damage without adequate time for healing and recovery. I stayed off such practices. Consequently in 2017, when the race started, I was feeling as though I was running in the plains. I have been repeating this protocol ever since. I prepare in the plains and rest ahead of a race at altitude,’’ Amit said.

Following the first-place finish at the 2017 La Ultra The High, in 2019, he was the top finisher among non-Ladakhi runners in the 72 kilometre-Khardung La Challenge (KC). He covered the distance in 9:22:50 to place eleventh among men. The next two years were claimed by COVID-19. Sports events came to a halt worldwide or were reduced to a trickle. In 2022, when the Ladakh Marathon returned after the pandemic, Amit and his friend Rakesh Kashyap, decided to attempt the inaugural edition of SRU. They planned to do it like a training run ahead of attempting the year’s Spartathlon in Greece. Joining them were Munish Jauhar and Anmol Chandan, also from Chandigarh, who had signed up to attempt the SRU and KC respectively. Amit followed the same acclimatization pattern as he did for the 2017 La Ultra The High. The race started well for him. At the 60 kilometre-mark, he was comfortably positioned in the pecking order, when he began having problems consuming the energy gels he had brought along. In the biting cold of altitude, the gels had become thick in consistency and when consumed, got stuck in his throat. He wanted hot water to wash it down. But at the aid stations, he passed, hot water was not available. He was told that he may get it further up on the way to Khardung La, at the aid station in North Pullu. But Amit sensed it was becoming a choice between pushing his luck and preserving his well-being for Spartathlon. He opted for the latter; he withdrew from the race. As did Rakesh, sometime later. Munish and Anmol had fine outings. Munish finished SRU in 19:47:40 to place seventh among 19 men in the fray; Anmol completed KC in 9:34:51 to place seventeenth among the 140 men in his category (source: 2022 Ladakh Marathon / SRU and KC results). Back in Leh and his throat condition addressed, Amit ran the event’s full marathon. In the weeks that followed, both he and Rakesh flew to Greece and completed Spartathlon.

By now Amit was sure that he would return to Ladakh for SRU. For the 2023 edition of SRU, he commenced training in mid-June. Besides his training runs, he worked out using the altitude mask. At the gym he frequented, he kept the treadmill at a good incline and walked with the altitude mask on. Each session with the mask lasted between 40 minutes to an hour. He did this twice a week. Once again Rakesh and Anmol joined him on the trip to Leh; this time all three would be running SRU. As the event drew close, Amit was sure that he was going to complete it within the stipulated cut-off time of 22 hours. Within that expectation, he set himself three options. The first was aggressive – cover the 122 kilometres in 15 hours to 15 hours and 15 minutes. Second, keep it sub-16 hours. In case both of the above proved tough, then do a sub-17. Third – complete the race at any cost. “ I have a habit of challenging myself,’’ Amit said over coffee at a café in Leh on September 11. Besides his goals in terms of overall timing for 2023 SRU, he divided the race into sections – Kyagar to Khardung, Khardung to North Pullu, North Pullu to Khardung La, Khardung La to South Pullu and South Pullu to Leh – to evolve a strategy and assign expectations. He planned to cover the first 50 kilometres in five hours and was happy when on race day, the stretch was actually done in five hours, 20 minutes. From Khardung to North Pullu, he had estimated a duration of three hours. It too was managed in and around the planned time. By now he had 50 per cent of the race in the bag and was the race leader. But the section from North Pullu to Khardung La proved tough.

The group of runners Amit was in – the first batch of the race – had left Kyagar, late evening on September 7. Aside from the odd street light at settlements like Khalsar and Khardung, the road wound on and uphill in utter darkness. By the time Amit commenced tackling the uphill from Khardung village to Khardung La, it was past midnight. The North Pullu-Khardung La portion came some hours after that. Sizable gaps separated the runners. Some proceeded alone; some stuck together. With traffic suspended for the duration of the race, it was quiet. One heard the sound of athletes breathing, the swishing of wind cheater fabric and the sound of shoes on gravel, as person passed by. An occasional nuisance were dogs, some of them, territorial. Race officials, moving up and down the road, chased the animals away. Viewed from far, sole stamp of runner’s presence in that vast, dark mountainous landscape was, each person’s headlamp. In between, one saw the brighter solar lamps of aid stations. Amit was ahead of everyone else, all by himself. “ I was feeling exhausted. I was shivering like hell. I had on, two pairs of gloves, three jackets and two caps. I was finding it difficult to drink water from the bottle,’’ he said. Amit reached the 17,618 ft-pass almost an hour later than what he had planned. The pass is a tricky place. Given the stretch spanning North Pullu to Khardung La as the place where many people withdraw due to exhaustion, reaching the pass in SRU, represents a milestone achieved. But with that can come a loss of appreciation for where exactly one is. The pass is high in elevation and bitterly cold. There is an aid station at Khardung La, where one can hydrate, get some nourishment and also rendezvous with drop-bags positioned in advance. Runners like Amit treat Khardung La carefully; they don’t let the milestone bit get into their head. Hanging around unnecessarily at the highest part of the race does nothing useful to the body. The emphasis is on shedding elevation. With the environment quite cold, oxygen level at the pass known to be lower than at sea level and his body feeling fatigued, Amit picked up a glass of hot soup from the aid station at the pass and quickly moved on. Ahead lay the long descent to Leh.

Amit does strength training thrice a week. He had trained for long descents. He was prepared for the downhill that follows Khardung La. But even he miscalculated what his needs may be, that September 8 dawn. It was a miscalculation on the logistics front. Layering and de-layering is how athletes functioning at altitude manage their attire to stay efficient. It is an act that seeks to strike a balance between protection from the elements, the temperature of one’s surroundings and the warmth, the body naturally generates as it works. Amit forgot to keep a drop-bag in advance at Khardung La so that he could de-layer in anticipation of the descent and the need of such faster movement to have less layers getting in the way. Minus drop-bag to leave his layers in, he stayed imprisoned in piles of clothing and gear that had served its purpose. So even as he exited Khardung La without wasting much time, he was bulky and hauling weight. He had on his upper layers, two layers on his legs, two pairs of gloves, two caps, hydration pack and trekking poles. Simply put, he couldn’t take advantage of the descent and run. He had kept his next drop-bag at South Pullu, several kilometres away on the Leh side. When on tired legs, every ounce of weight is acutely felt. Try running with too many layers on and one’s cocoon of clothing risks becoming unbearably warm. Till South Pullu, he moved inefficiently.

Meanwhile behind him, on the northern slopes of Khardung La, Amit’s friends were coping with a vastly different experience. Neither Rakesh nor Anmol own altitude masks. They had trained for SRU without it. According to Anmol, he compensated for the absence of such a gadget by resorting to high repetition interval training in the plains, which has the effect of improving respiratory efficiency. All that seems to have gone well. In retrospect, what happened after their training in Chandigarh was hugely different for the trio. In the pre-race acclimatization phase in Leh (11,500 ft), Anmol’s path and that of Rakesh, diverged sharply from Amit’s. Rest is very important in acclimatization. “ Amit does not do anything before a race at altitude. He rests. I reached Leh on August 28 and from then till around September 5, I piled on 70 to 80 kilometres in training. I don’t know why; that’s my style and it had worked for me in 2022,’’ Anmol said adding, “ Rakesh also put on similar mileage.’’ This time, the approach didn’t work. When this writer met Amit, Anmol and Rakesh in Kyagar, they appeared relaxed and in good spirits. But according to Anmol, at the start line of SRU late evening September 7, he was on tired legs. He realized he hadn’t recovered from all that running around in Leh.

The night of September 7, for about 30-35 kilometres since race commencement, Anmol and Amit were together. Then Amit pushed ahead. Around 60 kilometres covered and on the long ascent to Khardung La, Anmol began experiencing dizziness. He tuned into the sensation and decided to get it checked. Near North Pullu, he consulted the medical team that was present there with ambulance alongside. His oxygen saturation had dropped. He was otherwise feeling alert. It was very cold and so he was asked to try walking some more to see if the oxygen saturation level improved. Anmol figured that may not be viable. Such a walk would only be uphill given Khardung La was still some distance away. The terrain and direction of travel wouldn’t allow an improvement in his oxygen saturation unless he stopped or lost elevation. “ I told myself this is not a Kumbh Mela, something that happens only once in several years and therefore having to be done right now at any cost. I can always come back to try SRU again. I decided to quit the race there,’’ Anmol said.

Rakesh too gave up. But in his case, he may have misjudged his predicament. Rakesh’s exit from SRU was reportedly after some more distance (than Anmol) covered and it manifested as a collapse. Around the time of this incident, there was a bus carrying the baggage of KC runners (at 3AM that day, KC had commenced from Khardung village) and some runners who had retired from SRU, coming from North Pullu. Two of the runners in the bus helped this writer, recreate the scene. It was the morning of September 8. There were both KC and SRU participants running and walking on the road. The bus had just passed an ambulance parked by the roadside, when some distance away, one of the (above mentioned two) runners witnessed Rakesh collapse to his right side. Another runner, who was still in the race, stopped to tend to him. Upon reaching the scene, the bus driver halted the vehicle and honked to alert the ambulance behind. The runners from the bus stepped out to help. They told the racer who had stopped to assist Rakesh, to carry on as they were available. By then, the ambulance had arrived. Four people were required to help Rakesh into the ambulance. He kept saying that he was capable of continuing. But the doctor in the ambulance pointed to Rakesh’s collapse, put his foot down and said the race was over for him. “ It was between North Pullu and Khardung La, I would think 70 kilometres or so overall, from the start line of SRU,’’ one of the runners said. Rakesh received medical attention. He recovered. “ He is fine now,’’ Anmol told this blog on September 29. While on the SRU course, Amit knew nothing of what happened to his friends. He got updates only after he finished the race.

At South Pullu, Amit took 20-25 minutes to de-layer and have a warm cup of tea. Thus revitalized, he did a decent jog from there to Leh. “ I even pushed myself a bit,’’ he said, adding with a smile of satisfaction, “ if I remove all the time I lost to resting, and just aggregate the time spent moving, I clocked around 15 hours, 20 minutes and 10 seconds.’’ In all, over the 122 kilometres covered, Amit took three major breaks – at Khardung village, North Pullu and South Pullu. End to end, including any rest he may have availed, Shabbir Hussain of the Indian Army’s Ladakh Scouts regiment (he started the race one and a half hours after Amit did, in the second batch), won the 2023 SRU in 15:27:53. Amit would like to come back to Ladakh and improve his timing at SRU. “ There are some races, which are close to my heart. SRU is one of them. The finish line, located in Leh’s main market, is a fantastic experience. When I crossed the finish line, besides the spectators, there were people coming out from nearby shops to congratulate me. The congratulations in town continued the next day too,’’ he said.

(The author, Shyam G Menon, is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai. While the running community knows Amit as Amit Gulia, his official name – and the way it appears on race results – is Amit Kumar. At La Ultra The High, his name appears as Amit Chaudhary.)