Late August-early September, this blog got to spend time in Leh interacting with the organizers of the Ladakh Marathon, some of the runners arrived to participate and the people in town. The event comprises two ultramarathons, a marathon, a half marathon and shorter runs. Here’s a glimpse into the ecosystem of an engaging, still evolving event:

What makes the Silk Route Ultra and the Khardung La Challenge tricky?

Locations make marathons different. According to Dinesh Heda, for those not residing in the Himalaya, it is tough to replicate in the training phase, all the challenges one may face in the Silk Route Ultra (122 km) and the Khardung La Challenge (72 km). One can address endurance and accumulate elevation. But there is nothing possible as regards high altitude and weather. The altitude one touches in the Himalaya is serious; it brings in its wake reduced oxygen levels and biting cold. Alongside, there is the unpredictability of weather conditions. Things can change at short notice. Plus, during the course of the two ultramarathons (the longer Silk Route Ultra starts in the evening; the Khardung La Challenge at around 2AM), the athlete experiences cold to very cold conditions followed by the dry, warm weather of a morning in Leh. Because nature is dynamic, no two runs offer identical experience although the broad parameters may be the same.

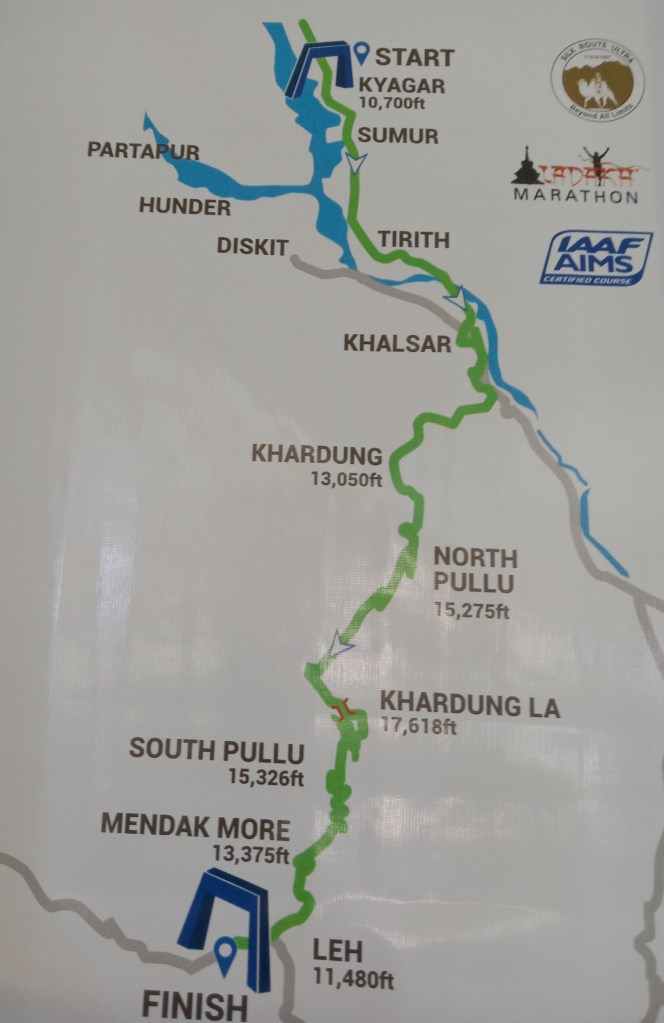

People who assume that the Khardung La Challenge’s 72 kilometres is just another 30 kilometres more than a marathon and therefore very doable, overlook altitude and weather, Dinesh who is a senior runner from Goa, said. Not to mention – there is the overall cut off and the individual stage cut offs, which must be met. This is what makes the Khardung La Challenge challenging and the Silk Route Ultra even more so. In the latter, which measures 122 km overall, two things get frequently overlooked by runners. While Khardung La Challenge starts from Khardung village, the Silk Route Ultra commences another 50 kilometres away, at Kyagar. That’s more than a marathon at altitude run, by the time participants join the regular Khardung La Challenge route. Second, while Khardung village to Khardung La is an uphill, same goes for the Kyagar to Khardung section. In other words, by the time Silk Route participants reach Khardung to tackle the regular Khardung La Challenge route (the two races converge at Khardung with the Silk Route Ultra leaders reaching there around the same time the Khardung La Challenge kicks off), they are already on tired legs. Dinesh attempted the Silk Route Ultra in 2022. Unable to meet the stage cut off at a particular portion of the course, he had to DNF (Did Not Finish). To his credit, Dinesh who has done the Khardung La Challenge multiple times, has accepted the outcome. In 2023, he was back in Leh, not for that unfinished business with the Silk Route Ultra, but to attempt again, the Khardung La Challenge.

An interesting blend

An emergent trend seen at the Ladakh Marathon is that of running the Khardung La Challenge and then following it up with the event’s full marathon. Dinesh has been doing this for a while. He was introduced to the practice in 2016. That year, Dinesh was in Leh for the full marathon when he saw Dharmendra Kumar from Bengaluru tackle both the Khardung La Challenge and the marathon. “ Dharmendra was the first runner I saw doing this combination in Ladakh,’’ Dinesh said. He commenced the practice in 2017. Today quite a few runners do this mix. When contacted, Dharmendra Kumar put the blend of ultramarathon and marathon, in perspective. “ It was a race just sitting there, waiting for you to try it,’’ he said of the marathon that beckoned following the Khardung La Challenge and a good night’s sleep. “ The idea was to do the marathon at an easy pace and enjoy the outing. That’s what we are here for, isn’t it? To run and enjoy the experience,’’ he said. What additionally engages is the difference between the two races. An ultramarathon is a personal experience. The runners may be separated by significant distance, there is a sense of being in one’s own cocoon, the route has long uphill sections, the weather may be unpredictable and there is always, the strain caused by higher altitudes. On the other hand, the marathon in Leh provides a sense of community when running with so many people around. The route has an uphill only towards the end, the weather is generally stable and after that tryst with really high altitude the day before and a good sleep thereafter, the marathon feels enjoyable to run. Plus, there is cheering. “ You take it like a recovery run,’’ Dharmendra said, adding that he was in no way discounting the inherent challenges of a marathon at altitude. It is just that when you run the marathon after the Khardung La Challenge, there is also an element of enjoyable relief and recovery at play. He was clear that the motive wasn’t to add kilometres and brag about the distance accumulated. After all, in the world of ultramarathons, 114 kilometres (the aggregate of the Khardung La Challenge and the marathon) is not big. The attraction is the relaxed pace of a recovery run and the enjoyment of being in a marathon with people around.

The invisible risk

Being an event at altitude, medical support is critical for the Ladakh Marathon. A variety of agencies – among them, the Indian Army and the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) dispatch their ambulances and ambulance crew to support the event. The event also has a medical partner. Since its inception, the Ladakh Marathon has had its share of medical emergencies. Significantly, it has stayed free of any fatal incident. In the case of the Silk Route Ultra and the Khardung La Challenge, participants have their oxygen saturation and pulse rate recorded twice by the organizers. The first checking is at the time of bib collection; the second happens before actual commencement of the race. Major variations are flagged and a runner may be held back from racing. Besides ambulances available along the way, there is the army’s medical station at Khardung La. With all this monitoring and the additional support of the race’s medical partner for a given edition, Chewang Motup, owner of Rimo Expeditions, which organizes the Ladakh Marathon, believes that the hosts are doing their best to contain risk. But there is one angle no organizer or race director can control and that is – concealment of medical facts by participants and poor appreciation of the risks attached to high altitude. At the race expo, Motup was seen speaking to runners, checking on their preparations and informing them of the need to respect altitude and follow the acclimatization protocol. He does not have a magic wand to flush out what runners won’t state openly.

Participation levels

In 2023, fifty-one persons were registered for the Silk Route Ultra and 261 for the Khardung La Challenge. Although podium positions are still dominated by local runners who are used to the altitude and the weather, the number of participants from elsewhere in India and abroad, have been growing. In all, the whole event spanning the two ultramarathons, the marathon, the half marathon and the shorter runs was converging nearly 6000 people to Leh this year. As P. T. Kunzon, former president of the Ladakh Buddhist Association (LBA) pointed out, the marathon has become a prominent fixture in the tourism calendar of Ladakh. Given its dates are in September, an otherwise lean period for tourism in Ladakh, the marathon has the effect of prolonging the tourist season. But it is two other factors that matter more from a business point of view. First, every runner in town is required to acclimatize well and this means, a longer period of stay in Leh. Some runners arrive with their families (in 2023, there was, according to the organizers, one family with 14 people running various distances at the Ladakh Marathon). For hotels and restaurants, this is a blessing happening as it does, in the tapering portion of the tourist season. Second, as denizens of the world of active life style, runners may wish to explore the outdoor activities Ladakh has to offer like trekking and camping (before or after the marathon). This is good news for people operating businesses around such activities. Compared to this, the tourist arrivals of Ladakh’s peak season mostly belong to the sight seeing sort. It is worth nothing that in 2023, while the number of people coming from outside Ladakh to run the two ultras, the full marathon and the half marathon had risen, the year’s tourist season till then had seen a fall in arrivals.

If one were to sense direction from how the Ladakh Marathon and the tourism around it have evolved (it has graduated from a marathon done and dusted in one day, to two ultras, marathon and smaller runs spanning as of 2023, four days), the mood is one of becoming a festival around the active life style. In 2023, besides the Ladakh Marathon, a football tournament was also scheduled to happen in the same period. This growth to being a multi-day affair is not the only emergent trend about the Ladakh Marathon. In the initial period it was a lonely walk for the event organizers, Rimo Expeditions. Over time, local authorities have come around to supporting the marathon. In Leh, local businesses with products and services relevant to the running community, keep the marathon in mind. “ We have people walking in to buy things in September,’’ Jigdol, proprietor of Himalaya Adventure Store in Leh, said. According to the organizers, on all the four days of the event, the roads earmarked for the races stay closed to traffic during the hours of the competition to ensure smooth passage for the runners. “ I prefer a road closed to traffic. As it is, I would be tired from the running. Watching out for traffic on top of that, would be making things needlessly complicated,’’ one ultrarunner told this blog at the Ladakh Marathon expo. On the Kyagar-Leh section, even the army – an active participant in the Ladakh Marathon with its pool of strong runners – suspends its convoys for the duration of the ultramarathons, Motup said. The communication support for the two ultramarathons is provided by the Signals Regiment of the Indian Army. In 2023, on the Kyagar-Leh route of the two ultramarathons, the regiment was set to have nine communication vans parked at regular intervals along the way. It is critical infrastructure for a race requiring proper monitoring of participants and medical assistance on call.

Many cities in India host marathons but the general attitude seen is one of finishing an avoidable chore and reverting to the Indian normal of traffic, rat race and money-making. Ladakh is a small place and its annual marathon, although big by local standards, is small compared to the marathons of the plains. But the ecosystem of support the event has acquired – it includes local authorities, the military, local businesses and local villages – is noteworthy.

A challenge in 2023

Leh has two major road links to the outside world. The most popular one is via Manali in Himachal Pradesh. The other is via Srinagar and Jammu. A lot of the materials needed to host the annual marathon reaches Ladakh from the plains. The goods travel by road. In 2023, the monsoon caused havoc in Himachal Pradesh. Besides causing a high number of deaths, it destroyed houses and wrecked the road network. September, the month in which the Ladakh Marathon occurs, is just outside the usual months of rain south of the main Himalayan axis (Ladakh is to its north). For a marathon, required materials should start moving at least a month in advance. In 2023, such logistics into Leh was hit by the natural calamity in Himachal. Shipments to Leh for the marathon got stuck between Shimla and Manali. A team had to be dispatched from Delhi, which then repacked the goods onto smaller vehicles and rerouted it through the few roads still open, to Jammu. There, it was transferred to trucks for passage to Leh via Srinagar. Some stuff had to be airlifted adding to costs. The kits offered to participants in the event’s ultramarathons are quite attractive and contain T-shirts, jackets, thermals etc. Orders had been placed as early as April-May. Given the challenging logistics scenario, things were still coming in even as the marathon’s expo got underway at the NDS Stadium in Leh. Nature stays an unpredictable and non-negotiable entity not just during the races in Ladakh but even in the preparations to hosting an event.

Before their race

Hanna Gogoseanu lives in Cluj-Napoca in Transylvania, Romania. She has been running regularly for the past three years or so. About two years ago, she happened to see a documentary on Ladakh on National Geographic. That was how she got to know of the Khardung La Challenge. It became a goal to aspire for. At that time, Hanna hadn’t run a proper marathon. So, to qualify for the Khardung La Challenge, she completed two marathons and in February 2023, commenced training for the race in Ladakh. For a taste of altitude, she spent time in the Carpathian Mountains of Romania but those heights are nothing compared to the Himalaya. Landing in Leh in the middle of August 2023, her first couple of weeks was tough. Besides the strain of altitude, she found the atmosphere dry. She developed nose bleeds. On August 31, when this blog met her at the race expo, she said she had begun getting used to the surroundings and had commenced her training runs. She knew she was due for an adventure and was looking forward to it.

This year, Maik Becker had with him Igor Kirsic from Switzerland and Marco Kuchhirt from Germany. For both Igor and Marco, it was their first visit to India and Ladakh. Both of them were into running but neither had done an ultramarathon at this altitude before. As Igor explained, he could accumulate elevation during training in the Swiss Alps but could do nothing about altitude, which is the irreplicable quantum when training for a run in the Himalaya. A triathlete, Marco had been to several Ironman events before. But he reserved complete respect for altitude, saying one cannot predict what lay in store. The duo was hoping to trek a bit as part of acclimatization, before reporting for the Khardung La Challenge. Maik on the other hand, was an old hand at the Ladakh Marathon and other races in India. A known Swiss ultramarathoner who travels the world to run, he had done the Khardung La Challenge a few times before. In 2023, he was set to attempt the Silk Route Ultra.

By the time of the race expo, Ashwini Ganapathi had been in Ladakh for over a month. She arrived on July 25. “ Five of us had planned to do a self-supported 100 kilometre run in the first week of August. We were to do it from Manali but we had to shift to Ladakh because of weather issues there,’’ she said. Apart for the 100K run, she had also planned a three-week vacation with her husband and a few treks. “ In Ladakh, we did the self-supported run of 100 km from Pang to Tso Moriri. It took us 27 hours to cover the distance. It was more of hiking than running. We drank water from the streams along the route,’’ Ashwini said. She also did a few motorbike trips apart from the treks to help in the acclimatization process. “ Ladakh is very dear to me. I have been visiting Ladakh for many years now,’’ she said. In 2019, Ashwini had done the 72 km Khardung La Challenge and finished second among women. That same year she also did the event’s full marathon. On preparations for the 2023 race, she said, “ I think my training for Silk Route has been good. I am familiar with the Silk Route course. Nevertheless, it will be a challenge to do it at night. The race starts at 7 PM. From 8 PM to 5 AM it will be dark.’’

Shikha Pahwa reached Ladakh in the end of August. As part of her acclimatization, she went for a hike to South Pullu at a height of 14,000 feet. She walked the way up and ran the course down. No stranger to Ladakh, in 2017, she had done the Khardung La Challenge and emerged the winner among women. In 2018 she completed the 111 km-race of La Ultra The High. “ In 2019, I did their 222 km-race but had to give up after 212 km as weather turned for the worse. Last year, I did the 111 km again. In June this year, I did the UTMB Mozart 100 in Salzburg, Austria. The official distance was 106.3 km. I was the only Indian participant and completed it in 19 hours and 56 minutes. For the Silk Route Ultra, I am banking on my experience in running in Ladakh. But weather can be an issue,’’ she said.

For Satish Gujaran, his first few days in Leh were trying. By the evening of his arrival, he had a splitting headache. He decided to take Diamox and continued the recommended dose the next day. By now, he had loss of appetite and was feeling nauseous. From the third day onward, his condition improved. He suspects, the episode may have been the result of him resting on day one in his closed hotel room instead of an airy ambiance. Over the following days, Satish commenced running locally. When this blog met him September 2 evening on Leh’s Mall Road, Satish had begun doing trips to Khardung La to get used to that higher altitude and get a feel of how walking and running at the pass and its immediate slopes may be like. “ On the day I arrived I found it difficult to walk to the hotel. Now, it’s much better,’’ Satish, a popular figure in running and someone who has completed the Comrades ultramarathon in South Africa many times, said. He felt that running Comrades and running in Ladakh couldn’t be compared. Altitude is a totally different beast. In a reversal of the trend of Indians going to South Africa to run Comrades, Satish wishes to bring interested South Africans to Indian destinations and marathon locations like Ladakh.

A beautiful Surly touring bike parked at the door of its owner’s office on Chanspa Road and a conversation with the owner about cycling, revealed a small detail. Leh resident, Tenzin Dorjee, was due to run his first half marathon at the 2023 Ladakh Marathon. “ My neighbour was in the army. But even after leaving the military, he continued to run. He was my inspiration,’’ Tenzin, who manages a travel company, said. He has been running for the past five years. He has been cycling for a longer period; during the COVID phase, he toured a lot on his cycle within Ladakh. In the following years, he cycled in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh. According to him, the Ladakh Marathon has had a salutary effect on local running with more people in Leh stepping out nowadays for a morning jog or run. Asked why the active lifestyle was late catching on in these parts, Tenzin attributed that to life in the mountains being a naturally active one and hence people not seeking out exercise as a separate avenue to physical fitness. That has changed with the onset of new perspectives to living; it received further impetus after the pandemic, he said.

In July, Anmol Chandan had earned a podium finish (third place) in the open category for men at the 2023 IAU 100KM Asia Oceania Championship, held in Bengaluru. In 2022, he had completed the Khardung La Challenge. This year, along with his friends, Amit Gulia and Rakesh Kashyap, he was set to attempt the Silk Route Ultra. Amit reached Leh on August 29. “ We have been clocking miles,’’ he said of the training runs the trio did locally. Usually doing 6-7 kilometres a day, they did around `16-17 kilometres on one day and also made a trip to Khardung La on motorcycles. The pass felt cold that day. “ It’s going to be how you feel on race day,’’ Anmol said, adding that he intends to have a strategy in place for the Silk Route Ultra but also provide room for flexibility. Both Amit and Rakesh have completed Spartathlon.

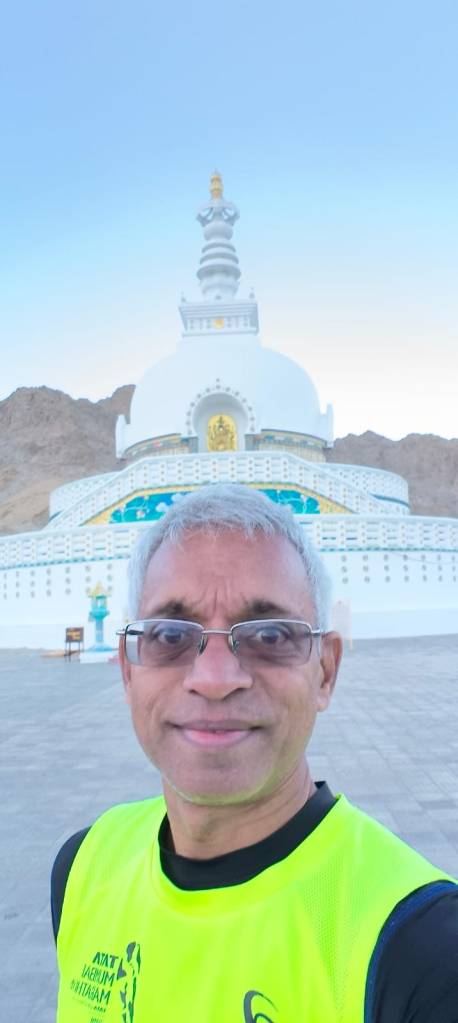

For many runners attempting the two ultramarathons within the Ladakh Marathon fold, the crux of the whole course was Khardung La and its immediate neighbourhood. This segment signified the zone with maximum altitude and lowest oxygen levels on the ultramarathon route. Runners hired cars and visited the pass to get used to the altitude and do mild training runs / walks around there. Dinesh Heda was among those not doing pre-race visits to Khardung La. Instead, after two days of natural acclimatization in Leh, he headed out in the opposite direction from Khardung La; to Shanti Stupa in Leh and the modest height gain it offered. Although he had a strategy for the race, he wasn’t a fan of the world’s fascination for measurement and data. He preferred to listen to his body. To perfect that link, Shanti Stupa sufficed. In his mid-fifties, Dinesh’s approach seemed one of reserving his running on race day for the flats, gentle gradients and downhill portions. Plus, be efficient without tiring oneself on the Khardung village-Khardung La stretch and try reaching the pass with some saved time on hand. In this, he knew that he wouldn’t be running near Khardung La, which is the hardest section. Up there, he would be walking as best as he can. “ I think it’s better to walk the uphill sections,’’ he said. Consequently, while training, he was focused more on maintaining his efficiency in brisk walking. Similarly, between performance and preservation, he preferred the latter. There were a couple of other reasons too for not stealing off to Khardung La before the actual race. Even if you visited the high pass so, there is no guarantee that conditions would be the same on the day of the race. So, why obsess with the pass and make it grow in one’s head like a formidable objective? Besides, Dinesh liked some things to stay unknown for a sense of discovery on race day. And no matter what the outcome on race day, he planned to be there for a celebratory beer in Leh with his friends.

The pass at the centre of the two ultramarathons

For most people today, Khardung La is the world’s second highest motorable pass and in Leh, a coveted objective tourists like to visit as a landmark in altitude reached in the neighbourhood. Simply put, it is all about altitude, vehicle, travel by road, the thin air of the pass and photos taken as proof of having been there. End of story. For Ladakhis however, that isn’t the case. Khardung La was for centuries, part of the summer route on the Silk Route to Central Asia. According to Chewang Motup, owner of Rimo Expeditions (it organizes the Ladakh Marathon) the Silk Route’s junction beyond the borders of Ladakh was Morgo. It had two routes of access from Leh. In winter, caravans proceeded to Morgo via Shyok village on the banks of the Shyok River. Although the river’s name is drawn from its capacity to spread gravel, there appears to be an element of death also associated and that could be because in olden times, the caravans to Morgo had to cross the Shyok River multiple times. River crossings can take a toll on animals and humans. In summer, this route becomes unusable because glacial melt causes the river to bloat. Consequently, the summer route from Leh to Morgo went via Khardung La. Motup recalled how in his childhood it had been a three-day trip on horseback from Kyagar, his home village, to Leh. It took another two days to Srinagar, where he attended school.

In the years past, the northern side of Khardung La used to be glaciated. Caravans via Khardung La operated till almost the mid-1970s, Motup said. His grandfather had gone a fair distance on the Silk Route. In 2002, as part of an expedition, Motup made it to the Karakorum Pass via Shyok. He was the third generation of his family to stand there. The motorable road from Leh to Khardung La, which everyone takes for granted these days, made its appearance only in the late 1970s. Just beyond the pass, there used to be a bridge that was – like many things Khardung La – acclaimed for its altitude. It no longer exists; the gap it bridged has been filled and concreted. Even with a road in place by the late 1970s, Khardung La wasn’t an easily accessible spot for visitors to Leh. It was a restricted area. Much later, when Nubra was opened to the public along with Dahanu (also called Aryan Valley), Pangong and Tso Moriri, the tourist destination called Khardung La was born. On either side of Khardung La, on the approach to the pass, lay North Pullu (on the Nubra side) and South Pullu (on the Leh side). Pullu in Ladakhi means a shepherd’s shelter. Long before they acquired their contemporary names, Motup said, North Pullu was known as Spang Chenmo while South Pullu was referred to as the pullu for Ganglas and Gonpa villages. Specific to the race (Khardung La Challenge), 2018 is widely recognized as having been a tough year for participants. There was rain on the approach to the pass and at the pass it was blizzard like conditions with very low temperature.

That time we run through

It is what decides podium finishes at races; it is what all runners live by (even the ones wishing to be free of its pull). Meet time. These days at marathons, time is measured using mats, which one steps on and side antennas that one runs past. The start and the finish, being most critical and requiring certainty of recording, typically feature both mats and antennas for redundancy. Mats are useful where a large number of people are involved, which is the case at the start line of a race. Time stations along the way, are served by side antennas and they suffice – especially in ultramarathons like the Silk Route Ultra and the Khardung La Challenge – because past the start line, clusters split and runners get spaced apart. The Silk Route Ultra will have six timing stations – at the start, at kilometre 25, at Khardung village, at Khardung La, at Mendak Mor and at the finish. For this race at altitude featuring a modest number of runners (both Silk Route Ultra and Khardung La Challenge put together), the service provider, Sports Timing Solutions, will work with a small crew in a format resembling a relay. Given the equipment used is imported and was designed for use in cold countries, the cold weather at stations like Khardung La won’t be a problem. What may pose difficulty is altitude; more precisely the effects of altitude on the people manning the stations (they have to be there till the last runner goes through). According to Amir Shandiwan, partner, Sports Timing Solutions, the company has learnt from its previous experience in operating at altitude in Ladakh. Aside from making sure the timing equipment and the people manning it are alright, the other thing to take care of is the availability of telecom network coverage for data transmission. Each year, this is assessed afresh on the mountainous route of the two ultramarathons. On September 5, the Sports Timing Solutions team was due to check out connectivity on the route. They had dongles from multiple telecom service providers to add redundancy into the system. As further back up, each timing station will have the provision to download the recorded data into a USB, so that in the event of any weakness in network, the data may be physically transported to the nearest point from where onward transmission is possible. To wrap up – one’s timing in the two ultramarathons may be just a series of inanimate digits; delivering it, however, entails some hard work.

The aid stations and a story of community participation

A unique aspect of the Ladakh Marathon is the participation of the local community in race arrangements. The route of the two ultras within the portfolio of races at Ladakh Marathon – Silk Route Ultra and Khardung La Challenge – are connected. The Silk Route Ultra is an extension of the older Khardung La Challenge with its start located 50 kilometres further up the road. Between Kyagar, where the longer 122-km ultra starts and Leh (the finish point), there are 21 aid stations. Except the aid station at the highest point enroute – Khardung La, and the one at the very end, all the remaining aid stations are operated by teams drawn from villages along the route. Of the seven aid stations between Kyagar and Khardung (from where the Khardung La Challenge commences), the first and third are managed by Sumoor village, the second by Lagzhum, the fourth by Khalsar and the fifth, sixth and seventh by Kyagar. Thereafter, the first four aid stations on the Khardung-Leh stretch are operated by Khardung village and the fifth and sixth by Kyagar village. Aid stations from the seventh to the thirteenth on this stretch are managed by teams from Ganglas and Gonpa villages. The last aid station, the fourteenth on the Khardung-Leh stretch is usually managed by a business enterprise in Leh close to that point.

The fourteenth aid station, located at Khardung La, is a crucial spot and is managed by a team drawn from the trekking staff of Rimo Expeditions. They spend roughly four hours on Khardung La, the highest and coldest point of the course, providing support to the runners passing through. However, the aid station that stays open longest is typically the seventh one on the Khardung-Leh stretch, Motup said. The above architecture of participation by villages, is noteworthy. In September 2023, there were 51 runners registered for the Silk Route Ultra and 216, for the Khardung La Challenge. According to Motup, the angle of carrying capacity wasn’t yet a bother because Khardung over time has added more accommodation facilities. And as for any strain on race infrastructure and monitoring due to enhanced participation, Motup pointed out that the longer Silk Route Ultra had debuted only after several years of holding the Khardung La Challenge. It was a conservative extension of the course’s length. Not to mention – the emphasis has been on sustaining and improving an existing race before adding another to the portfolio.

Sponsors yes but preference for those appreciating the event’s uniqueness

The high level of community support has meant, Motup setting matching expectations for his sponsors. He is clear that the Ladakh Marathon cannot be approached by sponsors in the same fashion they would, a city marathon. Notwithstanding what a sponsor may want by way of marketing and brand promotion, events in Leh come with non-negotiables like the limits and possibilities of local geography, unpredictable weather conditions, sensitive environment and modest size of race. Respect for these parameters may mean, the regular compulsions of brand promotion and marketing, requiring to compromise. For instance, a potential hydration partner cannot simply supply bottled water, end its engagement there and hope for publicity. At many marathons, plastic bottles generate garbage and littering. Water must therefore be handed out in cups to those requiring a drink. Sometimes, the realities of Ladakh and the involvement of the local community may also mean sponsors needing to go the extra mile. In 2022, the Tata Group, which was a partner that year, left behind a remarkable legacy – they built a reservoir for Khardung village, something utterly useful in Ladakh, which is a high-altitude cold desert. This year, it is hoped, Bisleri would build a reservoir for Kyagar village. Motup’s expectations don’t end there. He would like any sponsor interested in the event to also help in creating and sustaining Ladakhi talent in running. It may be recalled that for years, Rimo Expeditions has supported the growth of a team of runners from Ladakh; they travel to the marathons of India’s plains, have secured podium finishes and one of them – Jigmet Dolma – made it to the Indian women’s marathon team. Motup acknowledged that while there were those wishing to support the marathon, he had to let go of many such opportunities because they didn’t satisfy the overall paradigm employed.

(The authors, Latha Venkatraman and Shyam G Menon, are independent journalists based in Mumbai. Our thanks to all those who spared the time to talk to us.)